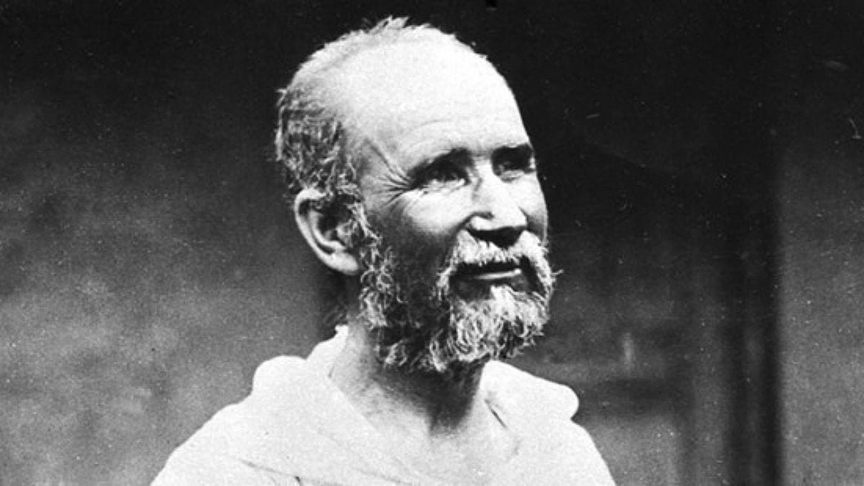

St. Charles de Foucauld was ordained a saint just one year ago on May 15, 2022. This Frenchman was murdered in Tamanrasset, Algeria, in 1916 where he lived in a hermitage among the remote Tuareg people.

At this point, eyes may glaze over. A saint who was a hermit? In the Saharan desert? What possible relevance does this have to my life?

Actually, it may be quite relevant.

For example, for the many parents concerned about a child who has left the faith, one might consider the young Charles de Foucauld, a man who called his Jesuit boarding school “detestable,” was known for his wild ways with food, drink, and women, and was kicked out of his first overseas assignment with the French army because he had brought his mistress along with him, among other infractions.

Or how about those who worry that their efforts in life and faith are producing little fruit? Here was a saint who hoped to establish an order of followers but never did in his lifetime. And in the Muslim village where he lived and offered Mass, he converted not a single soul.

It was Dorothy Day who famously remarked, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” Day had great respect for saints, but she realized that often we put them on marble pedestals, giving us an excuse to believe we could never be like them.

St. Charles de Foucauld invites us to rethink some of our assumptions.

Born into an aristocratic family in France in 1858, Foucauld was orphaned as a 6-year-old. He was brought up by an indulgent grandfather; some biographers think perhaps a little too indulgent, resulting in an arrogant and willful young man who inherited sizable wealth when his grandfather died.

One of his biographers called Foucauld “a boastful, lazy, and dissipated second lieutenant.”

Eventually leaving Mimi, his mistress, Foucauld was able to re-enlist in the French army. But failing to gain permission for a project he planned, he left the service and began a one-year scientific exploration of Morocco that resulted in a well-received book.

After returning to France, Foucauld remained intrigued by the Jewish and Muslim peoples he had encountered in his travels in North Africa, and by the faith they had witnessed.

Along with that, and perhaps another point of relevance for Catholics today, was the attention and determination of his cousin, a woman named Marie de Bondy, who saw a spiritual depth in Foucauld and didn’t give up on him.

She invited him to visit a priest, Henri Huvelin, who eventually became his spiritual director. Would Foucauld be a saint today without his cousin’s persistence?

By 1886, Foucauld had returned to Catholicism, citing an “interior grace” that called and motivated him. If he believed in God, he wanted God to be the sole focus of his life.

It was still years before the future saint entered religious life. In 1890, he became a Trappist. But his searching wasn’t over.

In 1897, he left the Trappists and journeyed to Nazareth where he worked as a gardener and sacristan for the Poor Clare Sisters. From there, he returned to France where he was ordained a priest in 1901.

His attraction to the people of North Africa led him to Morocco where he hoped to establish a community that would be welcoming to people of all faiths or no faith. He attracted no followers to this community, and eventually went to Algeria, where he lived as a hermit among the Tuareg people.

He learned their language well enough to write poetry and translate the Gospel.

Today, there are about 2 million Tuareg people, descendants of Berber tribes who live across wide swaths of North and West Africa, particularly in Saharan regions. They are semi-nomadic and predominantly Muslim.

When Pope Francis canonized St. Charles de Foucauld, he called attention to the universality of his faith, living as a brother to all. In another example of St. Charles’ relevance to our time, he gave the example of one who is not a proselytizer, but rather a witness to the simplicity and love of Christ.

“His goal was not to convert others,” the pope said, “but to live God’s freely given love, putting into effect ‘the apostolate of goodness.’”

The pope said St. Charles wanted “Christians, Muslims, Jews, and idolaters” to consider him their brother by opening the doors of his house to all.

The saint was not martyred for his faith. Instead, he was one of millions of victims of World War I. When French soldiers stopped at his hermitage, the enemy descended in hopes of finding weapons and de Foucauld was shot.

People of faith say that we plant seeds of faith and often do not experience their fruition. This was true of St. Charles de Foucauld, who was not able to establish a religious community.

Today, at least five religious congregations, associations, and spiritual institutes draw inspiration from his life and work. Among these are the Little Brothers of Jesus, Little Sisters of the Sacred Heart, and Little Sisters of Jesus.