When the deadly tornados pounded Middle Tennessee on March 3, one of the communities it stomped through was the North Nashville neighborhood.

Roofs were torn off, walls collapsed, foundations cracked, flying debris punched holes in walls.

The damage still marks the path the tornado took through the neighborhood. Some people are still waiting for contractors to make the needed repairs to their homes.

But a tornado can change the shape of a neighborhood in more ways than one.

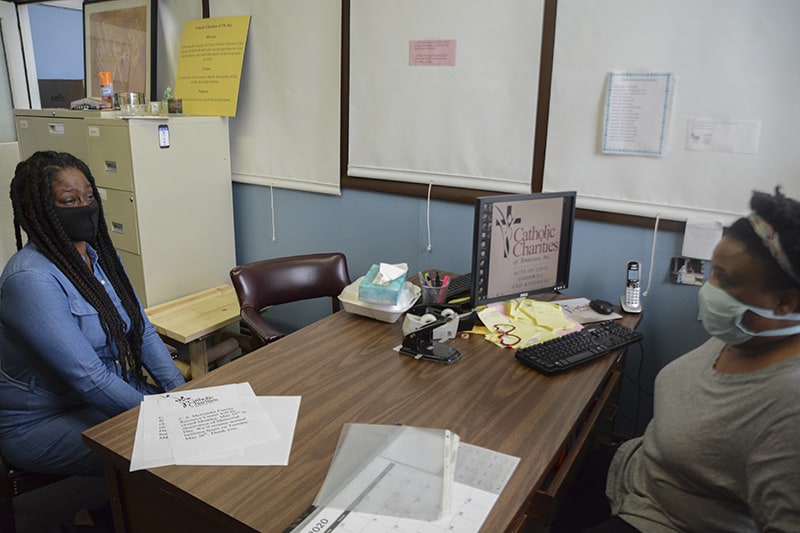

“We saw developers come in like sharks in the water,” said Alisha Haddock, director of community based services for Catholic Charities of Tennessee and director of the McGruder Family Resource Center in North Nashville.

“It was very, very distasteful and evil,” Haddock said. “They were trying to get people to sell when those people were vulnerable.”

For many of the homeowners in North Nashville whose houses were damaged in the tornado, “their hand was being forced,” Haddock said. “You don’t want to be under a mountain of debt because of the tornado. … But if I’m giving you half of what your property is worth, that’s not right.”

Gentrification is the latest in what residents consider a long assault on their community, the most damaging being the construction of Interstate 40 on a path through the middle of the neighborhood, displacing thousands of people and destroying thriving businesses.

A decline in the heart of Nashville’s African-American community followed the construction of the interstate, including lowered property values, rising poverty and incarceration rates, and a crippling of a thriving business and cultural district.

More than 50 years ago, it was the highway that disrupted the community. Today, it’s gentrification that is displacing residents and changing the character of the neighborhood.

Catholic Charities has partnered with other agencies to form a coalition “so we can support North Nashville homeowners holistically,” Haddock said. “We’ve put together funds and case management teams to help people to stay in the community so we can slow down the hyper-gentrification that we know comes in the wake of disasters.”

‘I decided to hold on’

In cities like Nashville with its booming real estate market and buyers looking for a home close to the action of downtown, a neighborhood like North Nashville, with relatively lower property values and close proximity to the city center, is an attractive option.

Ivery Frazier can walk along her block on 12th Avenue North, where she’s owned her home for 24 years, and see new homes sprouting, two- and three-story boxes known as “tall and skinnies.”

“I put my house on the market, just to see what would happen,” Frazier said. “I got calls from all over the country. … I decided to hold on.”

But since her house was damaged in the tornado, the pressure to sell has been increasing.

“I’m thinking I’m kind of vulnerable,” Frazier said. “We don’t know what to do to stop them. … They keep calling me.”

Even if she sold her home, Frazier’s not sure where she could find a new place to live that she could afford.

“I can’t afford to pay $2,000 or $1,500,” said Frazier, who is on disability. “I’m going to try to fight and stay here in my home and live peacefully.”

‘Our fight since day one’

The fight to stem gentrification is not new. “When Catholic Charities became lead agency at McGruder (in 2016), this has been our fight since day one,” Haddock said. “We wanted to find ways to slow it down. We were losing community members left and right,” as they were priced out of their neighborhoods because property values and their property taxes were spiking.

“We want them to survive and thrive in communities they know and love, neighborhoods they grew up in,” Haddock said.

“Part of what we need to do with Catholic Charities is to advocate for these people,” she said. “Don’t give up your family home. It can be fixed, and you can live there for years to come.”

The tornado has put pressure not only on homeowners but renters as well.

“In some cases, landlords are selling, leaving tenants to find a new place to live,” Haddock said. “That was happening within days of the storm.”

“It was really tough going for renters as well as homeowners. I’m sure it’s difficult for the landlords too,” Haddock said. “It was really difficult for everyone around.”

Stepping up with help

After the tornado struck North Nashville, there were even more immediate problems facing people – food and shelter among them – and the McGruder Family Resource Center was one of the places they flocked to for help.

The day after the tornado, “We opened our doors and we became a distribution site,” Haddock said. “We probably interacted with 3,000 people or more. And we were doing that without lights at McGruder Center for four days.”

While staff at the McGruder Center were helping people in North Nashville, staff at Catholic Charities’ offices at the Catholic Pastoral Center were helping people hit by the tornado in Hermitage, Donelson, Mt. Juliet, Lebanon and Cookeville. Staff from both locations were helping people in the Germantown and East Nashville communities.

Since the tornado, Catholic Charities has provided help with food and housing, working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to deliver the assistance people are qualified for, and finding contractors to repair their homes, said Wendy Overlock, disaster assistance coordinator and Loaves and Fishes program coordinator for Catholic Charities.

Catholic Charities added two staffers to help with the workload: Vickie York to help with tornado assistance and Kamrie Reed to provide counseling services for those affected by the tornado.

“Before they were hired, McGruder was in the middle of everything and anything that needed to be done for those families” in North Nashville, Overlock said. “The staff there was working 24/7 it seemed like.”

“North Nashville was hit particularly hard because they were on the edge already,” Haddock said.

Frazier was at home when the tornado swept through her neighborhood. “This is my second tornado,” she said, having also survived the tornados that smashed their way through Nashville in 1998.

“When I heard the siren,” Frazier said, “I knew it was real.”

She ran to the bathroom and jumped into the tub only to have a tree limb punch its way through the wall above her.

After the tornado passed, she stayed in her house through the night. “It was pitch black,” she said. “I didn’t step outside of my house until it was daylight.”

That’s when she saw all the damage. There were holes in the siding, the air conditioner was blown out of the window, her fence was destroyed, as was the electric meter for the house, and a tree in the back yard was heavily damaged.

“I guess the tornado was trying to lift the house up, but it didn’t,” Frazier said. Instead, it cracked the foundation.

“It was so much, I was wondering where was I going to start,” Frazier said. “My nerves were just shot. I was probably in shock.”

And she wasn’t alone. “A lot of people lost their homes completely,” Frazier said.

“It was like a dream,” she said. “I was blessed to be alive.”

Because of the damage, Frazier couldn’t stay in her home. “I was displaced for a couple of weeks. I was in my car.”

Eventually, she made her way to the McGruder Center, a place where Frazier has found refuge and a helping hand many times before. “They’ve made a big difference in my life.”

It was at McGruder that Frazier received help to earn her license as a hair stylist and later to receive training as a surgical tech. “I don’t think I’d probably be alive without McGruder programs,” Frazier said. “McGruder was with me every step of the way.”

After the tornado, she found help there getting food to feed her children and grandchildren, “which I appreciated,” Frazier said.

‘Picking up the pieces’

Catholic Charities continues to help scores of people who found themselves in circumstances similar to Frazier’s.

“We were kind of scrambling as we were picking up the pieces,” Haddock said. “We made a big push of providing food in North Nashville. It’s already a food insecurity area.”

“Without electricity, they can’t refrigerate food,” Haddock said, forcing people already strapped for cash to spend more on fast food.

Catholic Charities was able to help people whose homes were no longer safe to stay in temporary housing. “Vickie has put a lot of people in hotels,” Overlock said. “We’ve got a good rate to stay for a week or two.”

The temporary housing helped provide a bit of stability for people, “so they could get a shower, get to work,” she said.

Staff at McGruder and Catholic Charities also have been helping people find reputable contractors to repair their homes.

“A lot of people are worried about scammers,” Haddock said. “You have to be hyper vigilant, hyper aware of who you’re talking to, who’re you’re working with. … We need to make sure people understand the forms they are signing, the agreements that are being made.”

Some homeowners hit by the tornado were uninsured or underinsured and couldn’t afford to meet the deductible required by their policies, Haddock said. “We didn’t want them to have their deductible push them out.”

The agency arranged for volunteers to help with the tornado repairs.

The Saturday after the tornado hit, “we had 1,000 volunteers show up to help clean up North Nashville,” Haddock said.

But just when the community was starting to get back on its feet, it received another body blow.

“It was very busy and hectic those first two weeks after the tornado and then we were shut down by COVID,” Haddock said.

“It really put a burden on North Nashville tornado victims because everything would be done at a much slower pace,” Haddock explained. “We are moving more slowly and making sure we adhere to the safer at home guidelines and social distancing and still touching people in a way they can feel it.”

Pandemic deepens problems

“I can’t stress enough how COVID-19 came in and made things so much worse,” Haddock said. “After the tornado electricity was out for over a week for some of my neighbors. Then we move right into everybody stay in place … a global pandemic, and people started losing their jobs.”

“It really hit a lot of hospitality workers and people in the service industry,” Haddock said. “A lot of those people have been laid off. Now they don’t have any money to try to help themselves.

“COVID-19 touched everybody, but for communities like North and East and Hermitage and Donelson and Lebanon, you could see they were hit especially hard because they are dealing with the tornado and the pandemic,” she said.

Joshua Calvin, the workforce development coordinator at McGruder, went to work trying to identify sectors of the economy that were still hiring and helping people find new jobs, as well as helping people navigate the unemployment system.

Some of the jobs that were available, like stocking grocery store shelves, put people on the front line of exposure to the COVID-19 virus, forcing another difficult decision.

Taking those jobs might put themselves and their families at risk, Haddock said. “It was a revolving door of need and risk.”

‘It’s with them constantly’

It’s been nearly four months since the March 3 tornado, but Catholic Charities’ work with those most directly affected is just beginning.

“For us at Catholic Charities, it’s about more than providing people with a tarp and some food,” Haddock said. “It’s about helping people on this journey as survivors.”

“We’re looking at 12, 18 months of recovery. We could be looking at up to 24 months to recover,” Haddock said. “What we’re expecting is waves of survivors.

Beyond material assistance, Catholic Charities provides counseling services. “The stress of house repairs or someone getting hurt, the stress of those situations and add COVID on top of that, that’s why we have counselor on hand to help people,” Overlock said.

The emotional aftermath of a trauma like a tornado can linger, Overlock said, and new storms can trigger anxiety. “The people who are affected, it’s with them constantly,” she said.

“Alisha is checking on me and making sure I’m OK,” Frazier said. “Alisha keeps telling me, ‘Breathe, calm down, you’re alive.’”