Neil Stinson, RN, EMT, a parishioner at Holy Rosary Church in Donelson, works on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic in a dedicated unit at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

He dons layers of complicated personal protective equipment every shift and follows strict procedures for interacting with patients and staff. He advocates for patients who cannot receive visitors; he comforts those who might otherwise die alone.

But don’t call him a hero. “This is what we signed up for,” as nursing professionals, he said, and he’s honored to do the work.

“I appreciate the level of exposure our work is getting,” Stinson said, not to mention the lunches that various restaurants are sending to the staff. But the “hero” label makes him a little uncomfortable.

“While these times have been among the most challenging in my career, I feel so honored to be allowed at the bedside of these people afflicted with COVID-19,” he said. “I am very proud to be in service right now. And proud of the team I am a part of at Vanderbilt.”

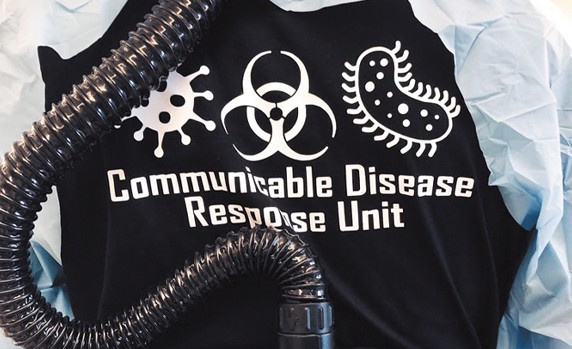

As a member of Vanderbilt’s Communicable Disease Response Unit, formed in 2014 to respond to Ebola, Stinson works alongside a team of experts to care for patients with potentially deadly infectious diseases.

“I’m drawn to be involved with the situation rather than play it from the sidelines,” he said. “I want to know the answer when things are scary.”

Stinson has also worked in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit and was recently accepted to join Vanderbilt’s LifeFlight team. For many years, he worked in the pediatric emergency room. Throughout his career, “I’ve had plenty of experience being with patients near death,” he said, but working with critically ill and dying patients in the COVID unit is different.

“We spend a huge portion of our days staying in touch with folks’ families,” he said, since visitors are not allowed in the unit. That often means arranging Zoom conferences on multiple devices and coordinating with multiple family members.

Stinson recalls one bedside scene that sticks with him: one nurse is holding up a tablet computer near the bedside of a dying patient while he holds another tablet with more family members from the hallway, then a chaplain calls in alongside a Spanish interpreter, because the patient is non-English speaking.

“There’s so many layers of complexity behind what is already a tragic and heartbreaking situation,” Stinson said.

Still, he’s grateful to be part of moments like these, living out his vocation. “I have felt called through the tradition of nursing to be in solidarity with the sick and suffering,” said Stinson, who attended Aquinas College School of Nursing.

“My prayers are mostly to stay in the moment in my work. To be awake, to pay attention and act where I am stationed. I pray to just be present in this time. “

It can be stressful and difficult work, and Stinson tries to be mindful of the beauty around him.

Watching the sunrise out the hospital window over the downtown Nashville skyline, walks around the neighborhood and gardening have been helpful, Stinson said, as well as putting his consumption of news and social media on a diet. The science of infectious diseases like coronavirus can’t be summed up in “a soundbite on Twitter or a meme on Facebook,” he said. “There’s not a blanket answer for everything.”

His morning practice of prayer has also been “absolutely necessary,” he said.

Stinson has practiced martial arts for many years, which has helped him compartmentalize and re-focus between work and home life. “In martial arts, you’re in a different place, with a uniform … you change what you wear, you change your mentality.”

Now, it’s a similar practice for Stinson when he gets home before he sees his wife Lauren and their three children. He enters through the basement, changes clothes and washes up before having physical contact with any of them.

Neil and Lauren, who also attended Aquinas nursing school and works as a hospice nurse, have been extra careful about interacting with others outside their household at this time. Even though he has not had any symptoms of illness, nor have any staff members in his unit, he still feels it’s best to proceed with caution.

COVID-19 is scary because of how highly contagious it is, Stinson said. “With COVID, if you’re in the room with someone and they sneeze, you have a good chance of getting it.”

That doesn’t mean a healthy person would necessarily become seriously ill with the virus, but they could carry it and infect someone else who might become critically ill. “Understanding how you fit into the whole webs of infection … it’s complicated,” Stinson said.

But one thing is simple: “The more exposure you have to the general public, the more likely you are to get any virus,” he said.

“I’m not sure how I feel about things opening back up,” and more people interacting on a regular basis, Stinson said.

With the continuously evolving situation of the coronavirus, “Nobody knows exactly what’s going to happen,” he said.

Nurses and staff in the COVID-19 unit at Vanderbilt University Medical Center must suit up with layers of personal protective equipment every shift. Adhering to strict safety protocols has prevented any staff members in the unit from getting sick while they treat seriously ill patients.