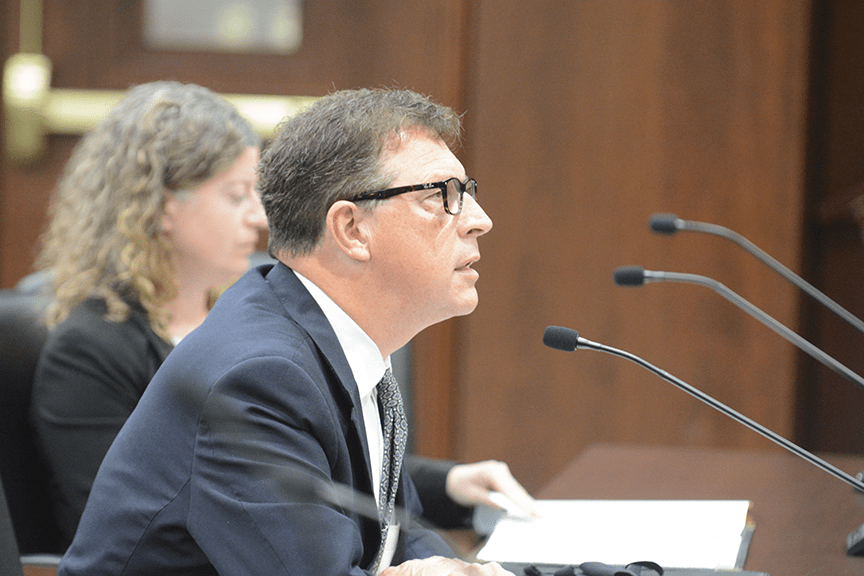

Refugees resettled in Tennessee make up only a small, specific part of the nation’s legal immigration system and contribute to their new communities, Rick Musacchio, communications director for the Diocese of Nashville and the Tennessee Catholic Public Policy Commission, told the General Assembly’s Joint Study Committee on Refugee Issues during a hearing on Thursday, Aug. 12.

“Refugees show tremendous resilience and contribute to Tennessee,” Musacchio told the committee in a prepared statement. “Their backgrounds are diverse. Some were doctors, scientists, or journalists; others have never used electricity. They seize the chance for a new beginning. They work hard in industries needing labor. They pay taxes, attend school, and serve in the military.”

Musacchio testified before the committee with Louisa Saratora, the State Refugee Coordinator for the Tennessee Office for Refugees, which is a department of Catholic Charities, Diocese of Nashville.

Although the committee’s title refers to refugees, most of its work has focused on the federal program that tries to find housing for unaccompanied migrant children while their application for asylum in the United States winds its way through the immigration system.

The committee has four charges: to evaluate the number of migrant children being permanently relocated in Tennessee by the federal government; to evaluate the number of children being flown into Tennessee and then relocated to other states; to evaluate how to increase transparency from the federal government regarding this relocation of unaccompanied migrant children to and through Tennessee; and to evaluate the impact, financial and beyond, on Tennesseans as it relates to the federal government’s migrant relocation program.

Musacchio and Saratora made the point to the committee that the unaccompanied migrant children are not part of the refugee resettlement program that Catholic Charities is involved in.

“The Refugee Resettlement Program is a longstanding but small and specific part of our nation’s legal immigration system,” Musacchio told the committee.

“The Refugee Resettlement Program only works with a limited number of people strictly defined in international law and recognized by U.S. law,” Musacchio explained. “The program primarily accepts as refugees, people who are coming from specifically designated parts of the world. Refugees are not admitted until they have successfully completed a very thorough vetting and screening process that typically takes a minimum of 18 to 24 months.

“People crossing the southern border of the United States, even if they may be seeking asylum under our nation’s immigration laws, do not meet the federal definition of refugee and are not part of the resettlement program,” Musacchio added. “Catholic Charities, Diocese of Nashville, does not place, transport, or relocate migrants or asylum seekers entering the country across the Southern border.”

Catholic Charities’ participation in the refugee resettlement program occurs at two levels.

“Our Refugee Resettlement Department is one of five agencies across the state – two in Nashville and one each in Memphis, Knoxville, and Chattanooga – that does the face-to-face, boots on the ground, work of assisting the fully vetted refugees brought to Tennessee as legal residents of the U.S.,” Musacchio said.

“Staff and volunteers follow a highly prescribed process to meet refugees at the airport (almost always commercial flights) and help them to settle in appropriate affordable housing and employment,” he explained. “Long history has shown that almost all refugees resettled through this program are self-sufficient within six months of arrival.”

In an answer to a question from a committee member, Saratora said numerous federal security agencies are involved in the vetting process for refugees before they are approved for resettlement in the United States.

“We only deal with legal residents in the United States,” Musacchio said of Catholic Charities’ refugee resettlement program. “These folks come in as the most thoroughly vetted immigrants in the country.”

The Tennessee Office for Refugees is a second department within Catholic Charities.

“In 2008, after the State of Tennessee stopped providing coordination and oversight of the resettlement agencies across the state, the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement contacted us to provide those services,” Musacchio said. “We established TOR, which provides administrative support on behalf of the state for the resettlement process in Tennessee.

“This department communicates with local governments and resettlement agencies in Nashville, Memphis, Knoxville and Chattanooga to assess each area’s capacity to accept refugees, and it communicates that information to federal partners including the State Department and the Office of Refugee Resettlement,” Musacchio said. “These federal partners use that information among other factors to determine where and how refugees are settled and supported. The number of refugees resettled through this program is set by the president of the United States each year.”

“TOR publishes quarterly reports on the refugee absorptive capacity and actual arrivals on the office’s website, tnrefugees.org, and sends copies to representatives of local governments, the chairperson of the Budget Committees of city or county legislative bodies, chairpersons of the House and Senate Committees on State and Local Government, and local refugee resettlement program directors,” Musacchio said.

Rep. Chris Todd of Jackson asked if a refugee would be considered self-sufficient if they were still receiving assistance from the state, such as through the Tennessee Assistance for Needy Families program or the TennCare health insurance program.

The federal definition of self-sufficiency stipulates that the refugee is receiving no cash benefits from the federal or state government, including TennCare, Saratora answered.

Refugees, as legal residents, are eligible to qualify for state benefits like any other citizen but must meet the same eligibility requirements that anyone else does, Saratora said. The refugee resettlement agencies in the state can help the refugee apply for those benefits but are not involved in determining whether they meet the eligibility requirements, she added.

Todd complained that the federal rules governing the refugee resettlement program leave little room for the state’s input.

“We still are in a position where the Tennessee taxpayers are funding some amount of assistance for refugees in this state without their choice,” Todd said. “It doesn’t come through the General Assembly. … That’s a problem so many of my constituents have with this program. By not going through the proper channels of the Legislature, we’re not giving our constituents adequate say in this process.”

Musacchio told the committee that a report created at the request of a similar legislative study committee has already determined that refugees contributed more in tax revenue than they consume in state benefits.

“A 2013 Tennessee General Assembly Fiscal Review Committee report examined federal cost shifting through the refugee resettlement program between 1990 and 2012. That report estimated that refugees provided more than $1.38 billion in revenue to the State of Tennessee during that period,” he said. “That is more than $633 million more in state revenue than they consumed in state funded services during the same time frame.”

Todd also asked about the resettlement agencies’ motivation for participating in the program. “Where is the incentive?” he asked. “Usually there’s money involved. … It seems like some folks are coming out with a pretty good living out of this.”

“This is a calling, this is a passion” for the people who work in refugee resettlement, many of whom came to the U.S. as refugees themselves, Saratora said.

The federal funding that refugee resettlement agencies receive for the program is grant-based and prescriptive, Saratora said. “They tell us what they want done with those dollars. There are multiple layers of local and national accountability,” she said, and expenses are not approved until they meet criteria set by the federal government.

The federal Office of Refugee Resettlement stipulates that 10 percent of a grant can be used to pay for the cost of administering the program, Musacchio said. The actual cost of administering the program is closer to 18 percent, and the difference is made up by generous donors to Catholic Charities, he said.

Catholic Charities has been involved in resettling refugees since it was founded in 1962, Musacchio noted. “Everything we do is rooted in the gospel message and Catholic social teaching,” he said. “We serve people not because they are Catholic, but because we are.”