This coming August marks not only the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II but also of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. From the very beginning, nuclear weapons have been controversial.

Controversy swirls around them again, as the nine nuclear-armed powers engage in a new arms race under the name of “modernization,” and as the United States and the Russian Federation have abandoned the treaties that for decades had regulated their deployment in the name of deterrence.

One question facing defense experts and arms controllers is whether in today’s geostrategic conditions the world can any longer trust in the kind of conventional arms control used since the 1960s to deter nuclear war, or whether the more reasonable thing is to aim directly at the elimination of nuclear arsenals.

For, as President John F. Kennedy said in 1963, not long after the Cuban missile crisis, nuclear disarmament is “the necessary rational end of rational men.”

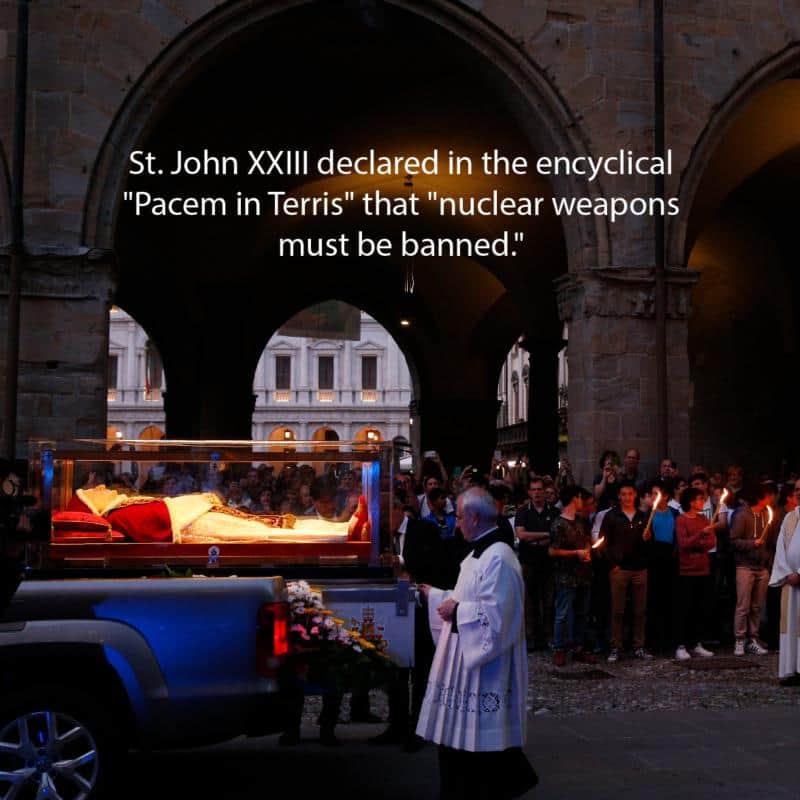

That same spring St. John XXIII declared in the encyclical “Pacem in Terris” that “nuclear weapons must be banned.” The goal of negotiation, he argued, ought to be “ultimately to abolish them entirely.”

Two years later the Second Vatican Council, after noting how “the horror and perversity of war is immensely magnified by the addition of scientific weapons,” solemnly declared, “Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.”

At the height of the Cold War, however, first St. John Paul II and then the U.S. Catholic bishops in their 1983 pastoral “The Challenge of Peace” allowed for a strictly conditioned acceptance of nuclear weapons for deterrence purposes only.

Earlier, however, St. John Paul on a visit to Japan had urged “that we will tirelessly strive for disarmament and the abolition of all nuclear arms.”

Thus, for 60 years the church’s view has been that abolition of nuclear weapons should be the goal of international nuclear policy.

In the years following the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989, it appeared that the policy of deterrence could continue be justified because, as the “Challenge of Peace” had prescribed, there was significant progress toward disarmament.

But, since the early 2000s that progress has stalled. The other strict conditions identified by the bishops have not been met. Arsenals, though reduced by 85%, remained far in excess of the minimal levels required for deterrence.

More important, the nuclear postures of both Russia and the U.S. contemplate the use of nuclear weapons against a variety of nonnuclear targets: chemical weapons, terrorism and even to avoid defeat in a conventional war. The firewall between nuclear and conventional forces, so central to the morality of nuclear weapons, had completely collapsed.

For those who cared about such things nuclear weapons were losing their legitimacy. For a number of years Vatican diplomats decried deterrence as “the chief obstacle” to negotiating the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Then, in 2017, Pope Francis “condemned” the use, the threat to use and the very possession of nuclear weapons, thereby proscribing deterrence.

The papal condemnation followed the adoption by a U.N. conference in July that year of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In September 2017, the Holy See signed and ratified the treaty.

The condemnation of deterrence is the clear teaching of Pope Francis in line with the teaching of his predecessors. He has publicly reiterated the condemnation several times, most recently on his visit to Hiroshima and Nagasaki last November. The 75th anniversary is time for American Catholics to make it their own.