(Editor’s note: This story was first published in the Tennessee Register on June 12, 2020.)

Five years ago, Dan and Michelle Schachle prayed to Venerable Father Michael McGivney, founder of the Knights of Columbus, to intercede with God to save their son, still in his mother’s womb, who was given no hope of surviving a life-threatening case of fetal hydrops.

When the condition, which is a dangerous accumulation of fluids throughout the body, disappeared, it triggered a long and complex process of evaluating whether a miracle attributable to Father McGivney’s intercession had occurred.

“It’s a strange thing to investigate, whether God has intervened in the world in an extraordinary way,” said Father Dexter Brewer, a Vicar General of the Diocese of Nashville and former Judicial Vicar of the diocese, who oversaw the local tribunal investigating the miracle.

“It’s all very formal, and very intense,” Father Brewer said of the process, which involved dozens of interviews, examinations of medical evidence, months of work, and a very specific submission process to the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

The process begins in the diocese where the miracle occurred, explained Brian Caulfield, the vice postulator of Father McGivney’s cause for sainthood.

The local bishop, in this case the late Bishop David Choby, appoints members of a tribunal to gather all the facts of the case.

“They weren’t leaving the question of is this a miracle to us,” Father Brewer said. “We collected the information and passed it along to the Vatican. We didn’t make a recommendation or judgment.”

The investigation began in 2016, and it was the first time in the Diocese of Nashville’s history that a miracle had been formally investigated.

“Basically, a miracle is defined as an extraordinary event that has no current medical or scientific explanation,” Caulfield said.

To verify an event is a miracle, “you have to prove two things,” Caulfield said. “The first thing is to prove this was a healing that’s not explained by medical science.”

The second is to clearly identify who people were praying to for their intercession, in this case, whether the intercession of Father McGivney was clearly invoked, Caulfield said.

Before the official investigation opened, Vatican officials visited Nashville to place the members of the tribunal under oath and walk them through the process. At the time, said Dr. Fred Callahan, “it was top secret.”

Callahan, a neurologist and close friend of Bishop Choby, was asked by the bishop to lead the medical side of the investigation.

Callahan was personally present for each of the detailed interviews with about 20 different Vanderbilt University Medical Center physicians who cared for Michelle Schachle during her pregnancy and after the birth of her son Michael, as well as other maternal-fetal medicine specialists familiar with the case.

Callahan had learned about hydrops as a medical student, “in the remote past.” He had to re-familiarize himself with the condition “so I could ask the right questions,” he said. “I didn’t want this to fail because of my failures.”

Callahan, with help from tribunal member Valerie Cooper, had to work diligently for months to schedule and conduct the interviews, navigate HIPAA privacy regulations to assemble medical records and reports, ultrasound imaging, and ultimately compile a full dossier of evidence to send to the Vatican.

Callahan said he felt the weight of the task, because “the medical portion of the investigation would determine whether it was a miracle.”

Intercession of saints

The other key part of the investigation was whether the miracle is truly attributable to the intercession of Father McGivney. “The Vatican had very precise questions about the timing and the prayers, who prayed when, and to whom,” said Father Brewer, the pastor of Christ the King Church in Nashville.

The tribunal needed “to see if there was a correlation between the prayerful petition and the medical cure,” said Callahan.

The Schachles were certain their prayers to Father McGivney resulted in God curing their son of the condition that almost certainly would have killed him before he was born or shortly after. They told the interviewers how they specifically prayed for the intercession of Father McGivney and asked so many others to do the same.

Knights of Columbus around the world had simultaneously been offering up prayers for Father McGivney’s canonization,the formal process by which the Church declares a person to be a saint and worthy of universal veneration.

The idea of praying to saints, holy men and women who have died, is a long tradition in the Catholic Church and recognizes the ongoing connection between the living and the dead.

“The early Church always encouraged people to pray for each other,” said Dr. Robert E. Alvis, Academic Dean and Professor of Church History at St. Meinrad Seminary and School of Theology in St. Meinrad, Indiana. “The path of holiness is both individual and communal.”

“We pray for our own dead, we pray to the holy dead, we pray for their intercession,” Alvis said, with the idea that “God bends his ear with special attentiveness to those who lived a life of holiness,” especially on behalf of the most vulnerable.

“Catholics, Christians, have always been encouraged to pray to God directly, to the saints, and for each other,” Alvis said.

“People may be more comfortable turning to an intercessor because they’re more relatable. … Often, we turn to a person who once lived, one with whom we have a personal connection,” said Alvis, such as the Schachles did with Father McGivney, because of their shared connection to the Knights of Columbus and care for children with special needs.

“Holy people in heaven are in greater proximity to God; there’s a sense they have a greater persuasiveness before God,” Alvis said. “When God responds to the petition of a saint, he honors that saint in some way.”

“Saints can, through their intercession, prompt God to cause a miracle,” Alvis said.

“God does act in this world; miracles do happen.”

Transformed by the outcome

Beyond witnessing the faith of the Schachle family, one of the most rewarding experiences of serving on the committee, Callahan said, was seeing how the medical team members who cared for Michelle and Michael Schachle “had been transformed by the outcome” of the case.

“From a medical perspective, there were things that happened that were not expected, and occurred outside of current medical knowledge,” Callahan said.

Multiple physicians recommended that Michelle Schachle terminate her pregnancy because the diagnosis was so bleak. “Our society has a lot of judgments about the value of life, and the disposable nature of life,” Callahan said.

Maybe after their experience with the Schachles, some of those physicians won’t be so quick to make that judgement, Callahan said.

After talking with the doctors, Callahan said, he could tell that this case “appropriately tickled their intellect, but even bigger, it changed their hearts.”

A gratifying ‘yes’

After the Nashville tribunal compiled all of its findings, sealed and tied in red ribbon, and sent them off to Rome, it was up to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints to review the information and make a recommendation to Pope Francis whether the case was indeed a miracle.

The tribunal’s findings first went to the postulator of Father McGivney’s sainthood cause, Andrea Ambrosi, a civil and canon lawyer in Rome, Caulfield said. He had the findings translated into Italian and then presented them to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

The postulator, who must be certified to present cases before the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, “puts together the strongest possible case, as any lawyer would, taking the facts and presenting them in the most convincing way,” Caulfield said.

After assuring that the record is in the proper canonical form, it is reviewed by a panel of medical experts, practicing physicians and medical professors in Rome, who aren’t necessarily religious, Caulfield said. With their review complete, “One day in Rome, they get together and cast their votes. Is this a miracle or not, can we explain this or not,” Caulfield said.

“It went through the medical commission pretty easily,” Caulfield said of the Schachle case. “That’s the huge hurdle.”

Next the case is reviewed by a theological commission that examines the question of whether the cure can be attributed to Father McGivney’s intercession, Caulfield said.

“They came down yes, there was more than ample evidence that Father McGivney was invoked exclusively,” Caulfield said.

Having cleared those hurdles, the case next moves to the pope for his final approval that a miracle had occurred that was attributable to Father McGivney’s intercession. Pope Francis issued that decree on May 27, 2020.

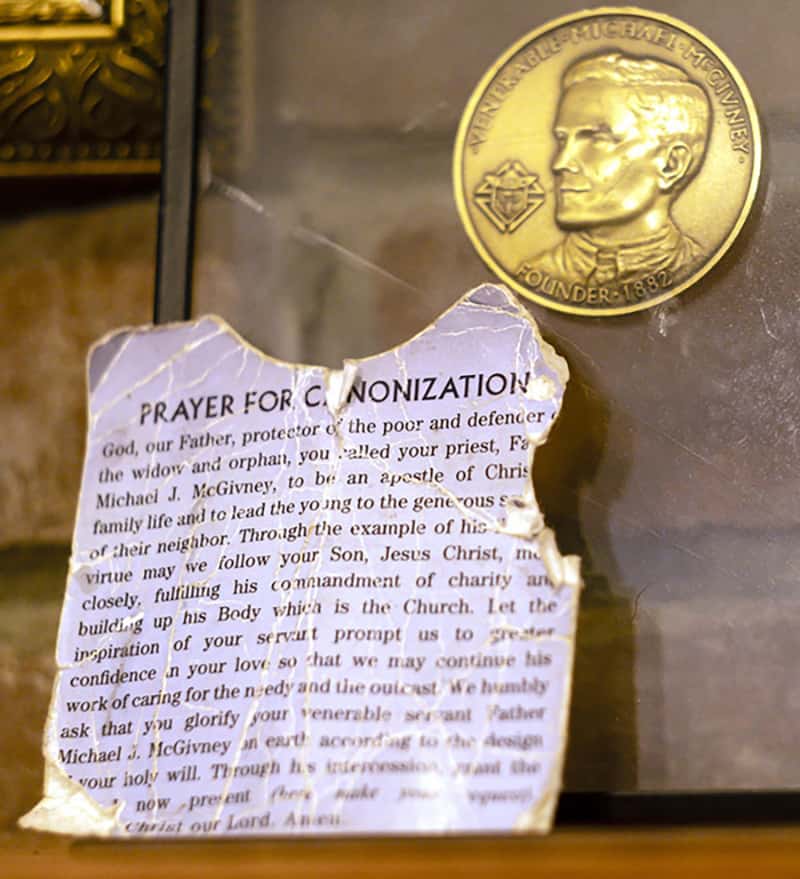

The formal beatification when Father McGivney will be bestowed with the title Blessed will occur during a Mass on Oct. 31 at 10 a.m. (CT) at the Cathedral of St. Joseph Cathedral in Hartford, Connecticut. The Mass will be celebrated in the Archdiocese of Hartford because that is where his sainthood cause was initiated in 1997.

A second miracle after the beatification must be confirmed before Father McGivney can be canonized as a saint.

Members of the Diocese of Nashville who served on the tribunal didn’t hear anything about the case for years. Callahan learned that Pope Francis had approved the miracle by reading a short piece about it in theNew York Times. The article didn’t mention the name of the family, but he knew it was the Schachles.

“It’s gratifying that the Vatican said ‘yes,’” this is a miracle, Callahan said. “I think they got it right.”

Andy Telli contributed to this report.