(Editor’s note: A version of this story was first published in the Sept. 4 issue of the Tennessee Register.)

Catholic families in the Diocese of Nashville were affected by World War II like every family in the country.

They fought on the front lines and in the air. They worked in factories producing material for the war effort. They lived with rationing of a host of products, including meat and sugar, rubber and steel. They anxiously awaited word about their sons, brothers and fathers fighting half a world away. They prayed for peace.

“There was no household in the country that somehow was not involved” in the war effort; they all knew someone who was in the service or who had died in combat, said Msgr. Owen Campion, a Nashville native and historian of the diocese.

Americans welcomed news of the end of the war with joy and relief. Emperor Hirohito announced Aug. 15, 1945, that Japan would surrender. He formally signed the surrender Sept. 2, 1945.

Four years of sacrifices, worry, battlefield horrors and millions of lives lost had finally come to an end.

The nation honors those sacrifices and the sacrifices of generations of veterans before and since on Veterans Day, Wednesday, Nov. 11.

James Cornelius “Connie” Summers, a Naval aviator and a 1939 graduate of Father Ryan High School, was on the South Pacific island of Saipan, preparing for the planned invasion of Japan when the war ended.

“We were happy as can be,” Summers, 99, said of the reaction to the end of the war. The invasion of Japan “was going to be horrible,” he said. “They took no prisoners. If they captured you, you were dead.”

After serving in Europe as part of the final push into Germany, John Burns and his twin brother Bob were at Camp Campbell on the Tennessee-Kentucky state line training for the invasion of Japan when the war came to a close. “It was a relief,” said Burns, a 1944 graduate of Father Ryan. “Seeing what we saw, we were getting ready to go back into the same thing.”

Going off to war

At the beginning of the war, Tennessee Catholics joined the effort along with the rest of the country.

In April 1942, Summers, who was working for the telephone company when the war started, headed to the recruiting station to enlist, hoping to be assigned to a construction unit to take advantage of his work experience.

But a recruiter stopped him on his way in and asked if would consider becoming a Navy aviator. Summers knew that required two years of college, and he hadn’t spent any time in college.

The recruiter told him not to worry about that. If he passed the test, the Navy would send him to college while they trained him to fly planes.

Summers passed the test but had one more obstacle. At his physical examination, the doctor discovered he had flat feet. “You’d be 4F if you were in the Army,” the doctor told him. “If you’re going to be a pilot, they’ll never check your feet again, so I’ll pass you.”

In the Navy, you weren’t a pilot, you were a Naval aviator, Summers explained. “A Naval aviator learned to be an aviator, bombardier and a navigator,” he said.

“I got my wings in June 1944,” and shipped out for the Pacific Theater, assigned to the crew of PBM patrol bomber, a large seaplane with a crew of eight enlisted men and three officers, Summers said. “It was a big, big airplane.”

As one of the junior officers, Summers would alternate between serving as the co-pilot and the navigator. Based in Saipan, his crew flew missions bombing Japanese ships from Korea to Okinawa, with several close calls along the way.

At the end of one mission, Summers’ plane ran out of fuel and had to land on the open sea, “which is not fun,” he said. The plane landed near a convoy of five American ships. While Summers and his crew stood on the wing of their plane and watched, 100 or more Japanese planes armed with 500-pound bombs swooped down on the convoy. “We watched them sink all five of the ships,” Summers said.

One of the Japanese planes headed toward Summers and his crewmates. “We all jumped in the water,” he said, and from there they watched an American fighter pilot swoop in at the last moment and shoot down the Japanese plane before it could drop its bomb.

Pushing into Germany

John Burns was a senior at Father Ryan High School in 1944, the captain of the football team.

“When I was in high school, when you would go to a football game hardly anybody was there,” recalled Burns, now 94. All of the men were either in the service or busy working a job to support the war effort, he said.

On the 18th birthday of he and his twin brother Bob in February, they received a letter directing them to report to Camp Forrest in Tullahoma for a physical. They were able to complete their senior year before reporting for duty the following August.

On Jan. 30, 1945, they shipped out from New York to join the war in Europe. They eventually ended up in Aachen, Germany, to join the 83rd Infantry Division, which had been decimated during the Battle of the Bulge, Burns said. “They had lost all kinds of people.”

The Burns brothers were tapped to be a bazooka team and saw combat as the Allied Forces made the final push into Germany.

“The Germans would be surrendering like crazy,” Burns said. “They were hungry. They wanted something to eat.”

When they would enter a village, they would be met by a woman with four or five children or a priest telling the Americans that the German soldiers had all left, Burns said. “They didn’t want the town torn up.”

Burns’ company was in Austria when Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945. He and his brother had been separated at the time, and Burns promised God he would never miss Mass if he could be reunited with his twin. It’s a promise he’s kept for 75 years and counting.

‘Nobody complained’

Back on the home front, life had changed as well.

“Everything was rationed,” remembered Jim Langdon, who was born in 1936 and was a school boy at Assumption School in Germantown during the war.

“Everybody had a little book,” said Langdon, who went on to teach at Father Ryan for 52 years. “You’d have rationing stamps in there. I’d watch Mama pull out stamps for different things.

“Meat was the hard thing,” Langdon said. “You could get hamburger, but don’t expect much else.”

Gasoline also was rationed. “You could only get so many gallons of gas per week,” he said. “But most people didn’t have cars.”

“You could not get tires,” Langdon added. “If you got a flat tire, you had to put a patch on it and go on. They rode on those tires until they were slick as glass.”

Fearful of air raids, blackouts were enforced at night and wardens would walk through neighborhoods reminding people to turn off their lights.

“The amazing thing is people went along with all that, no complaints,” Msgr. Campion said.

“People knew what the soldiers were going through, so nobody complained about it,” Langdon said.

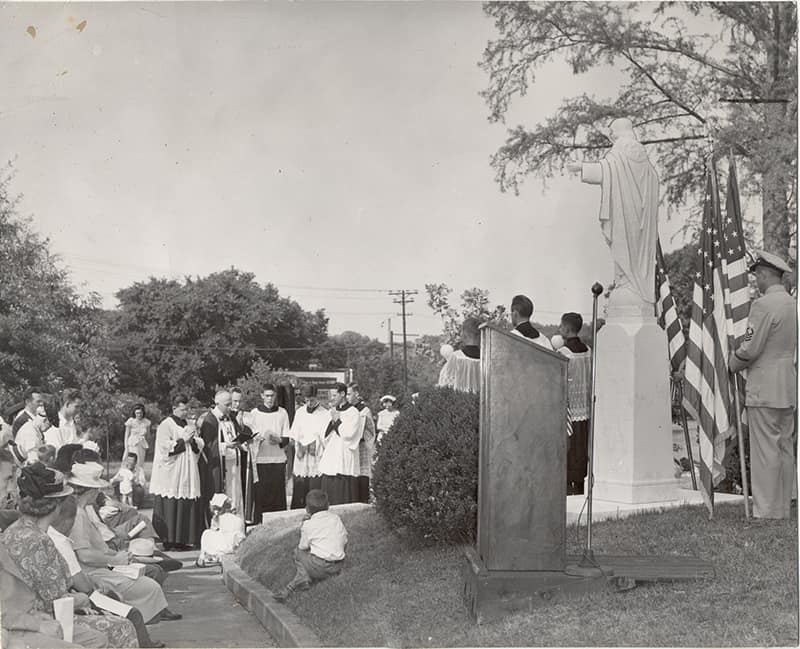

Middle Tennessee was home to several military installations that hosted training exercises, so Nashville seemed always to be filled with soldiers. And the Diocese of Nashville tried to meet their spiritual needs in parishes and out in the field.

The Jan. 2, 1944, edition of the Tennessee Register featured three front page photographs of diocesan priests with the soldiers. One shows a young Father George Rohling, kneeling next to a soldier in a field of high grass to hear his confession. Another photograph shows a Mass being celebrated outdoors under a tent.

Several priests of the diocese joined the military to serve as chaplains and accompanied the troops overseas on the front.

The USO and the Knights of Columbus sponsored dances for the soldiers at Father Ryan High School, which led to many romances and eventually marriages of soldiers from all across the country and young ladies from Nashville.

“The adults tried to make life as normal as possible,” Langdon said. But they couldn’t keep the war at bay completely.

Langdon’s oldest brother David was taken prisoner during the Battle of the Bulge.

“I was in school,” Langdon remembered. His teacher told him he needed to go home. “And I said, ‘Why?” She said, ‘Jimmy, just go home.”

On the short walk from Assumption School, Langdon topped a small hill. “At the top I could see my grandmother’s house. I saw a lot of people out on the porch. I didn’t know what was going on.

“We went into the dining room, my mother was sitting in a straight-backed chair and she was rocking back and forth and she was crying.,” Langdon remembered. “I didn’t know what to say or what to do. Someone finally said my brother was missing in action. That meant you weren’t coming back home.

“I can still see that,” Langdon said.

His brother survived the ordeal of spending time in a prisoner of war camp and did make it back home, Langdon said.

“Our family was lucky,” Langdon said. “We didn’t lose anybody.”

But his brothers and other relatives who were in the war rarely talked about their experiences, Langdon said. “Those guys had a lot of bad memories, especially those who saw combat,” Langdon said. “They would never talk about it.”

‘I’ve been lucky all my life’

After the war, life slowly returned to normal.

“When the war was over, these people were absorbed back into society and given jobs,” Msgr. Campion said of the veterans. “It’s amazing businesses were able to absorb them.”

Growth in the diocese was put on hold during the war but resumed in the post-war years. That growth included a surge in vocations to the priesthood among World War II veterans, Msgr. Campion said.

“There was quite a surge of priests who had been in the military,” Msgr. Campion said. “That was not only in Nashville but that was around the country,” Msgr. Campion added.

Burns was at Camp Campbell at the end of the war when he met four or five of his friends from Father Ryan who were playing football for what is now Austin Peay State University in Clarksville. He joined them at Austin Peay before finally returning to the family farm on Foster Avenue in Nashville.

Eventually, he and his brother bought a larger farm in the Triune community, which his family still owns. Burns is a parishioner at Holy Family Church in Brentwood, but every Wednesday he and his family attend Mass together at St. Patrick Church in Nashville, where he grew up.

“That’s all thanks to Dad,” said Burns’ daughter Teresa Creecy. “On Monday, he’ll give us a call, ‘Are you going to be at Mass?’”

After the war, Summers enrolled at Vanderbilt University on the GI Bill, but was still unsure of what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. “I had no idea what I wanted to do,” Summers said. “I knew I didn’t want to fly airplanes.”

A professor suggested he consider law school, and with just enough money left for college, he enrolled in Vanderbilt Law School in 1947 and graduated in 1950. He went on to have a distinguished career as an attorney and public servant.

He served as a hearing examiner for the Tennessee Supreme Court’s Board of Professional Responsibilities, president of the Young Lawyers’ Association of Nashville, and on the board of the Nashville Bar Association. Gov. Frank Clement appointed him as chair of the Governor’s Advisory Committee for the Establishment of Community Health Centers in Tennessee, which helped establish more than 30 centers across the state.

Summers has been president of the Nashville Mental Health Association, the Tennessee Mental Health Association, the Nashville Mental Health Center, and the Dede Wallace Mental Health Center.

A parishioner at St. Henry Church, Summers served on the boards of Catholic Charities of Tennessee, St. Patrick’s Shelter for homeless families, and St. Mary Villa Child Development Center.

Summers summed up his experiences: “I’ve been lucky all my life.”