Nearly from its founding in 1837, there were two poles in the Diocese of Nashville, which included the entire state of Tennessee. Nashville was where the diocesan governance was located, but Memphis was the vibrant heart of Catholicity in the state.

“Memphis was the tail that wagged the dog,” said Msgr. Owen Campion, a former editor of the Tennessee Register and a historian of the diocese. “Nashville was where the diocese was, but Memphis was where the action was, no doubt about it.” The Vatican recognized the strength of the Catholic community in Memphis and West Tennessee and the new Diocese of Memphis was established at a special Mass on Jan. 6, 1971.

The diocese originally planned to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its founding with a special Mass this month, but has moved the date to late spring because of the COVID-19 pandemic. There will be two 50th Anniversary Masses, one at 7 p.m. May 26 at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Memphis, and a second at 7 p.m. May 27 at St. Mary’s Church in Jackson.

‘Boom town’

The Diocese of Nashville’s first bishop, Richard Pius Miles O.P., had “a very daunting task,” Msgr. Campion said. When the diocese was established, “in the entire state of Tennessee, he was the only priest.” Bishop Miles called on his fellow Dominicans to help him build his diocese, eventually convincing them to take over Memphis’ first church, St. Peter’s, established in 1840. “They’re still there to this day,” Msgr. Campion said. Though younger than Nashville, Memphis grew quickly in the first half of the 19th century, and by 1860, its population of 22,000 had passed that of Nashville’s 19,000.

Much of the city’s growth was fueled by its location on the banks of the Mississippi River, a major artery for transporting people and goods, and its development as a major railroad hub, Msgr. Campion said.

“It was a boom town,” and the railroads were a key contributor to that growth, Msgr. Campion said.

As the city’s population grew, so too did its Catholic community. “There was a large influx of Irish. Then there was a large influx of Italians,” Msgr. Campion said. “At one time, Memphis had the largest community of Italian-Americans between Chicago and New Orleans.”

The city’s Catholic community had grown so large that after the Civil War there was talk of moving the episcopal see from Nashville to Memphis.

But then Memphis suffered several setbacks in the form of Yellow Fever outbreaks. “They were catastrophic,” Msgr. Campion said. “They had three yellow fever epidemics, which almost took the city out. There was such a horrendous loss of life. People fled and it created a reputation. People did not want to move there. Businesses did not want to move there.”

Catholic nuns and priests who stayed to care for the sick and dying, many of them succumbing to the Yellow Fever themselves, became heroes in the city, which showed its appreciation for years to come.

Eventually, the city of Memphis recovered. “It came back really vigorously,” Msgr. Campion said. “You move into the 20th Century, it definitely had recovered. It was booming again.”

A Catholic identity

As Memphis grew, so too did its Catholic population, in numbers and in prominence. “The Catholic community began to form a real identity and it was somewhat an identity different than the rest of the state,” Campion said. “Catholics in other parts of the state had not had that sort of privileged place.”

Besides individual Catholics who became prominent in the city, the Church itself carved out an outsized role for itself through institutions like St. Joseph Hospital, two Catholic colleges, Catholic high schools and elementary schools, a Catholic orphanage, a Catholic nursing home, and a growing number of parishes.

“It was just an established Catholic community,” Msgr. Campion said.

Talk resurfaced of moving the episcopal see from Nashville to Memphis, or of establishing a new Diocese of Memphis. “The question always was … can the rest of the state make it without Memphis,” Msgr. Campion said.

World War II put those discussions on hold. Nashville Bishop William Adrian resisted talk of forming a new diocese, arguing that the task at hand was building up the Diocese of Nashville to accommodate the growing Catholic population in the state in the post-War years, Msgr. Campion said. “There was a big boom in church building.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Church in Memphis and in the rest of Tennessee was caught up in the most important issue of the times, the Civil Rights movement.

The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. The Board of Education, which desegregated schools, “was a monumental moment in the history of Memphis,” Msgr. Campion said.

Desegregation wasn’t popular anywhere in the South, he said, but in some cities, like Nashville, the political and business leaders decided “we don’t like it, but we have to go with it,” Msgr. Campion said. In other cities, like Memphis, the leadership resisted desegregation.

At one time Memphis considered itself a rival of Atlanta and Dallas as major cities of the South, Msgr. Campion said. “My opinion is Memphis’ reluctance to accept segregation stopped its momentum,” he said. “I don’t think there’s any question about it.”

A rift between the city’s Catholic community and Bishop Joseph Durick grew as the bishop became a prominent voice in support of the Civil Rights movement. “He was strong on Civil Rights,” said Msgr. Campion, who later served as Bishop Durick’s master of ceremonies. “That made him very unpopular in Memphis.”

In the late 1960s, when talk resurfaced of creating a new diocese for West Tennessee, Bishop Durick didn’t fight it. “I think probably Bishop Durick felt … it was Memphis’ time.”

New diocese established

“The process to create a new diocese is quite extensive,” Msgr. Campion said. “They would have looked at it in many ways.”

One question to be answered was whether the new diocese would have strong enough finances to maintain itself, Msgr. Campion said. “It wasn’t a question of whether Memphis could do it, it was could Nashville survive.”

Another was whether the new diocese would have enough priests to serve the people. “Probably half of the priests of the diocese were from Memphis,” Msgr. Campion said. Convinced that the resources and the need were there, Pope Paul VI, on Nov. 18, 1970, announced the formation of the Diocese of Memphis, covering the 21 counties west of the Tennessee River, and the appointment of its first bishop, Msgr. Carroll T. Dozier of the Diocese of Richmond in Virginia.

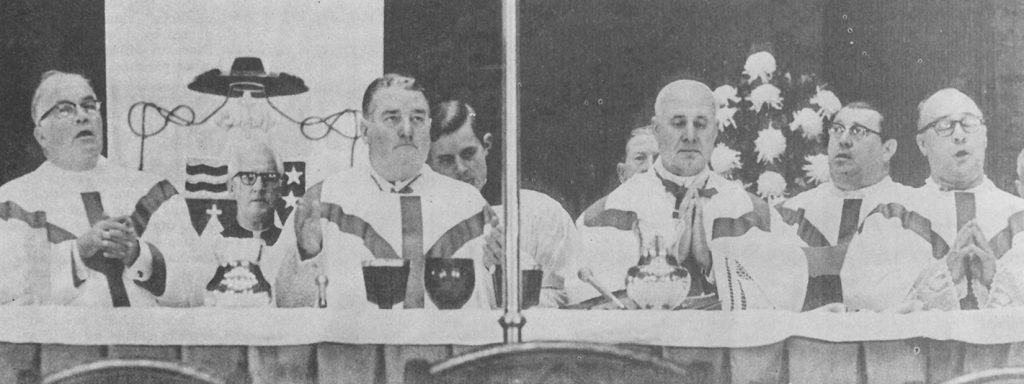

Bishop Dozier, who served in Memphis until 1982, was ordained as a bishop and installed, and the proclamation establishing the diocese was read during a Mass held Jan. 6, 1971, at the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis. Nearly 9,000 people attended.

“It was an enormous occasion,” said Msgr. Campion, who attended as a young priest. “They invited all the priests of the Nashville Diocese, so I went down for it. The hotel (where he was staying) was practically taken over with guests for that occasion.”

“It was a big, big thing,” he said. In his address at the end of the Mass, Bishop Dozier welcomed the people to the new diocese with an eye on the future.

“As we look to the future – and we are future-bound – we may ask ourselves, what kind of a Church shall we be? What kind of a Church do we want to be?”

“One in union with the Vicar of Christ, one dispensing the grace of God to all men, one anointing sorrow with sympathy, one of love and human kindness, a good Samaritan on the banks of the Mississippi. Is this not what we, this new Diocese of Memphis, wish to be? By the grace of God, so shall it be.”

The division of the two dioceses, worked out for both, Msgr. Campion said.

“The Memphis Catholic community is a blessing, it’s an example,” he said. “The Catholic people in Memphis have an enormous devotion to the Church, in every way. If you look at what they built down there, the image they created for the Church, absolute dedication, even heroism. It’s an image they created. It’s an image they created 150 years ago and kept going.

“The Catholic community … long ago has made itself an important part of the civic community,” Msgr. Campion said. “It’s an identity they should be proud of and one as a Tennessean that I am proud of.”