VATICAN CITY (CNS) — St. John Paul II, who died April 2, 2005, at age 84, was a voice of conscience for the world and a modern-day apostle for his church.

He had a philosopher’s intellect, a pilgrim’s spiritual intensity and an actor’s flair for the dramatic, making him one of the most forceful moral leaders of the modern age.

An estimated 4 million people paid their respects over several days to the pope who had led the universal church for more than 26 years. His funeral April 8 was broadcast around the world and drew more than a million people, including kings, queens, presidents and prime ministers, and representatives of many faiths.

Seeming to respond to the “Santo subito!” (“Sainthood now!”) banners that were held aloft during his funeral in St. Peter’s Square, his successors — retired Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis — respectively beatified and canonized him, after waiving the normal five-year waiting period for the introduction of his sainthood cause.

The first non-Italian pope in 455 years, St. John Paul became a spiritual protagonist in two global transitions: the fall of European communism, which began in his native Poland in 1989, and the passage to the third millennium of Christianity.

As pastor of the universal church, he jetted around the world, taking his message to 129 countries in 104 trips outside Italy — including seven to the United States.

Whether at home or on the road, he aimed to be the church’s most active evangelizer, trying to open every corner of human society to Christian values.

In fact, he laid out his vision of the church’s future and called for a “new sense of mission” to bring Gospel values into every area of social and economic life with a landmark document, the apostolic letter “Novo Millennio Ineunte” (“At the Beginning of the New Millennium”).

His social justice encyclicals also made a huge impact, addressing the moral dimensions of human labor, the widening gap between rich and poor and the shortcomings of the free-market system. At the pope’s request, the Vatican published an exhaustive compendium of social teachings in 2004.

Within the church, the pope was just as vigorous and no less controversial. He disciplined dissenting theologians, excommunicated self-styled “traditionalists,” and upheld church teaching against artificial birth control. At the same time, he pushed Catholic social teaching into relatively new areas such as bioethics, international economics, racism and ecology.

He led the church through soul-searching events during the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, fulfilling a dream of his pontificate. His long-awaited pilgrimage to the Holy Land that year took him to the roots of the faith and dramatically illustrated the church’s improved relations with Jews. He also presided over an unprecedented public apology for the sins of Christians during darker chapters of church history, such as the Inquisition and the Crusades.

As a manager, he set directions but often left policy details to top aides. His reaction to the mushrooming clerical sex abuse scandal in the United States underscored his governing style: He suffered deeply, prayed at length and made brief but forceful statements emphasizing the gravity of such sins by priests. He convened a Vatican-U.S. summit to address the problem, but let his Vatican advisers and U.S. church leaders work out the answers. In the end, he approved changes that made it easier to laicize abusive priests.

The pope approved a universal catechism as one remedy for doctrinal ambiguity. He also pushed church positions further into the public forum. In the 1990s, he urged the world’s bishops to step up their fight against abortion and euthanasia, saying the practices amounted to a modern-day “slaughter of the innocents.” His sharpened critique of these and other “anti-family” policies helped make him Time magazine’s choice for Man of the Year in 1994.

The pope was a cautious ecumenist, insisting that real differences between religions and churches not be covered up. Yet he made several dramatic gestures, including: launching a Catholic-Orthodox theological dialogue in 1979; visiting a Rome synagogue in 1986; hosting world religious leaders at a “prayer summit” for peace in 1986; and traveling to Damascus, Syria, in 2001, where he became the first pontiff to visit a mosque.

To his own flock, he brought continual reminders that prayer and the sacraments were crucial to being a good Christian. He held up Mary as a model of holiness for the whole church, updated the rosary with five new “Mysteries of Light” and named more than 450 new saints — more than all his predecessors combined.

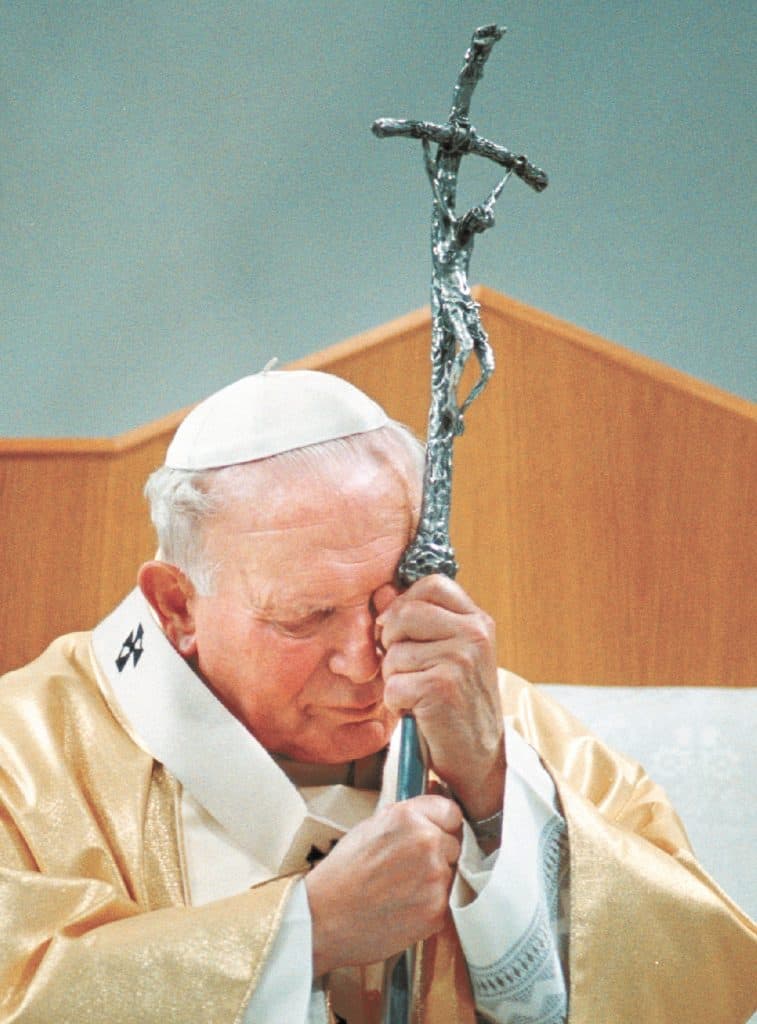

The pope lived a deep spiritual life — something that was not easily translated by the media. Yet in earlier years, this pope seemed made for modern media, and his pontificate has been captured in some lasting images, like huddling in a prison-cell conversation with his would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, who shot the pope in St. Peter’s Square May 13, 1981.

Karol Jozef Wojtyla was born May 18, 1920, in Wadowice, a small town near Krakow, in southern Poland. He lost his mother at age 9, his only brother at age 12 and his father at age 20.

An accomplished actor in Krakow’s underground theater during the war, he changed paths and joined the clandestine seminary after being turned away from a Carmelite monastery with the advice: “You are destined for greater things.”

Following theological and philosophical studies in Rome, he returned to Poland for parish work in 1948, spending weekends on camping trips with young people. When named auxiliary bishop of Krakow in 1958 he was Poland’s youngest bishop, and he became archbishop of Krakow in 1964. He also came to the attention of the universal church through his work on important documents of the Second Vatican Council.

Though increasingly respected in Rome, Cardinal Wojtyla was a virtual unknown when elected pope Oct. 16, 1978. In St. Peter’s Square that night, he set his papal style in a heartfelt talk — delivered in fluent Italian, interrupted by loud cheers from the crowd.

In his later years, the pope moved with difficulty, tired easily and was less expressive, all symptoms of the nervous system disorder of Parkinson’s disease. By the time he celebrated his 25th anniversary in October 2003, aides had to wheel him on a chair and read his speeches for him. Yet he pushed himself to the limits of his physical capabilities, convinced that such suffering was itself a form of spiritual leadership.

With the third-longest pontificate in church history, St. John Paul died at the age of 84 on the vigil of Divine Mercy Sunday. Divine Mercy Sunday had special significance for the pope, who made it a church-wide feast day to be celebrated a week after Easter. Pope Benedict beatified him on Divine Mercy Sunday, May 1, 2011, and Pope Francis canonized him on the same feast day, April 27, 2014.