From staff reports and Catholic News Service

Tommy Lasorda, the baseball Hall of Famer who managed the Los Angeles Dodgers to two world championships, had a soft spot in his heart for the Mercy Sisters of Nashville.

When they were looking to move to a new convent, Lasorda helped raised the money to make it happen.

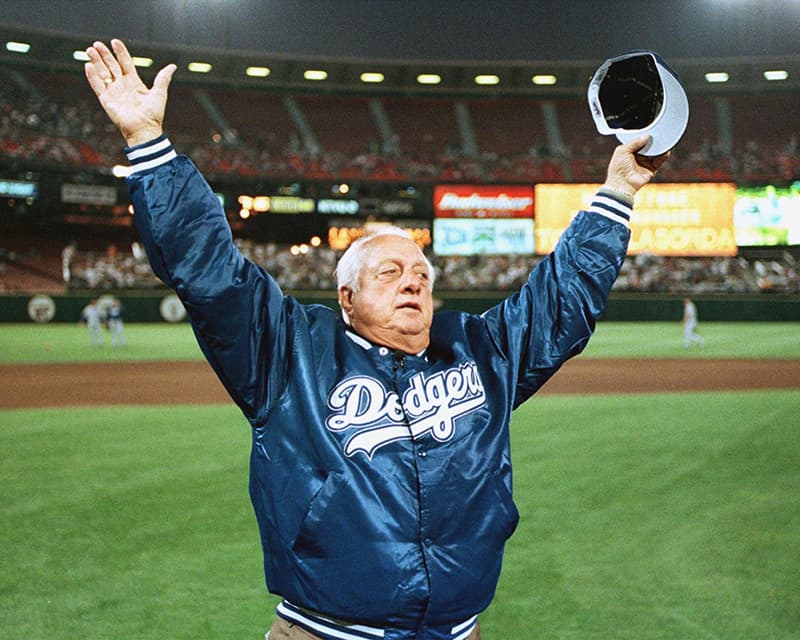

And years after the Sisters moved into Mercy Convent on Pennington Bend Road in Donelson, Lasorda continued his friendship with the religious order. “The Sisters always brightened up every time he came here,” said Sister Adamarie Kost, R.S.M., who was the coordinator of the Mercy Sisters’ St. Bernard Convent on 21st Avenue South and the Mercy Convent in Donelson during the transition. “It was like a visit from Santa Claus.” Lasorda died on Jan. 7, 2021, at a Los Angeles hospital an hour after suffering cardiopulmonary arrest at his home. He was 93 years old.

As a pitcher, Lasorda’s baseball career didn’t amount to much – an 0-4 career record with a 6.48 ERA over 58.1 innings playing two seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers and one with the Kansas City Athletics – but as a manager he shone, winning four National League pennants and winning 1,599 games, all with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

He was inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997, the year following his retirement as manager after 21 seasons, but he wasn’t done as a skipper, leading the U.S. men’s baseball team to a gold medal in the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.

In his retirement, he became an ambassador for baseball.

As much as he was an ambassador for the sport, Lasorda served as a self-styled ambassador for the Catholic faith. He grew up in the Philadelphia suburb of Norristown, Pennsylvania, where he attended an Italian parish, Holy Savior. In a 1989 interview, Lasorda said: “We were so poor, I wore shoes with soles so thin I could step on a coin and tell whether it was heads or tails.”

But Lasorda said on repeated occasions, “I’m proud to be a Catholic,” and pitched in to help numerous charitable endeavors.

In 1989, he learned that the Sisters of Mercy in Nashville needed financial support for a new convent. “They have dedicated their life to God so we need to give something back; everyone thinks Rome pays for these things,” Lasorda said. Lasorda’s connection to the Mercy Sisters was the late John A. Hobbs, a builder and developer who developed much of what is now known as Music Valley, including the Nashville Palace nightclub and John A’s Restaurant.

Hobbs met Lasorda through a mutual friend. “They just clicked. They became the best of friends,” Joe Hobbs, John A.’s son, told the Tennessee Register at his father’s funeral in 2019.

John A. Hobbs had a long-lasting friendship with the Sisters of Mercy and in particular Sister Mary Colman Burns, RSM, who had been his teacher at St. Ann School when he was a child.

She was the principal of Holy Rosary Academy when the Sisters were looking for a site for a new convent, and she reached out to Hobbs for help, Sister Adamarie said.

Hobbs and his business partners, Louis and Patrick McRedmond, purchased property on Pennington Bend Road and donated it to the Sisters, according to reporting in the Tennessee Register in 2019.

Hobbs brought Lasorda to meet Sister Mary Colman to discuss what the Sisters needed, and she took the lead in working with the two men to find a way to finance construction of the convent, Sister Adamarie said. “Sister Mary Colman did all the work on this. None of this would have happened without Sister Mary Colman Burns.” In the fall of 1990, Hobbs organized a benefit for the Mercy Sisters and Lasorda was one of the celebrities who participated.

At the time, Lasorda was trying to lose weight, and he turned the effort into a fundraising tool to benefit the sisters, said Sister Suzanne Stalm, R.S.M. The year after the Dodgers’ breathtaking upset win over the Oakland Athletics in the 1988 World Series, Lasorda, who said he had not stepped on a scale in eight years, weighed in at 218. He pledged to get down to 190 and collected $50,000 in pledges for the convent. He was aided by two of his stars, pitcher Orel Hershiser and outfielder Kirk Gibson, each of whom promised to contribute $10,000 if he lost 20 pounds, and then added to their pledge the other eight – which Lasorda accomplished. “He did lose the weight, so he did get that money, and he donated it to us,” Sister Suzanne said. “His financial contribution to the building of Mercy Convent was significant.”

The Sisters moved into the Mercy Convent in June 1991, Sister Suzanne said. “This convent has been a blessing to the Sisters of Mercy for the past 30 years.

Lasorda’s support of the Mercy Sisters continued after the convent opened. He would often visit the Sisters when he was in town visiting Hobbs.

In the small chapel of the infirmary of the convent is a stained-glass window that was donated by the artist who created it, Charles L. Madden, in memory of Lasorda’s son, Tommy Lasorda Jr., who died in 1991.

The Mercy Sisters of Nashville weren’t the only Catholic religious order or organization Lasorda supported. In 1994, when the Dodgers were still conducting spring training in Vero Beach, Florida, Lasorda emceed a dinner to benefit the St. Joseph School Foundation in Lakeland, Florida, the spring training home of the Detroit Tigers, which coincided with Detroit manager Sparky Anderson’s 60th birthday. At the dinner, Anderson, himself a Hall of Fame Catholic skipper, received a baseball autographed to him by St. John Paul II.

In a 1994 interview, Jim Leyland, then the manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates whose brother is a priest in Ohio, said he admired fellow Catholics Lasorda and Anderson most of all. They “have been successful for so long because they could adjust to the changes in the game,” Leyland said.

In 1985, Lasorda worked with Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley to help Carmelite sisters in Guerra, Dominican Republic, where the Dodgers had set up a development camp for promising Dominican ballplayers.

Lasorda and Cuban-born Dodgers super scout Ralph Avila rented a house where the Carmelites began to teach their first class of 35 children in 1985. Later, Lasorda bought them a bus. By the turn of the century, the Programa Comunitario Futuro Vivo school had room for 600 youths in vocational training and computer classes, with six students having gone on to join religious communities.

At a 1995 testimonial dinner in Philadelphia, Lasorda called his Catholic faith “very, very important, something I believe in strongly but don’t try to force on others.”

“I love my faith,” he said. “I practice my faith. It’s helped me a great deal throughout my lifetime.”