SEATTLE. The Catholic Church is working to promote healing and rebuild trust with Native American communities in response to revelations about mistreatment of students in Church-run boarding schools, a priest working on Native American issues for the U.S. bishops told an Archdiocese of Seattle gathering.

“This is heart stuff, not head stuff,” Father Michael Carson, assistant director of Native American Affairs at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said during an Oct. 23 program.

“It’s connection. Feeling the pain, the abuse, the suffering. … Do not be afraid to let the pain and frustration into your heart,” said Father Carson, a priest of the Diocese of San Jose, California, and a descendant of the Choctaw tribe in Louisiana.

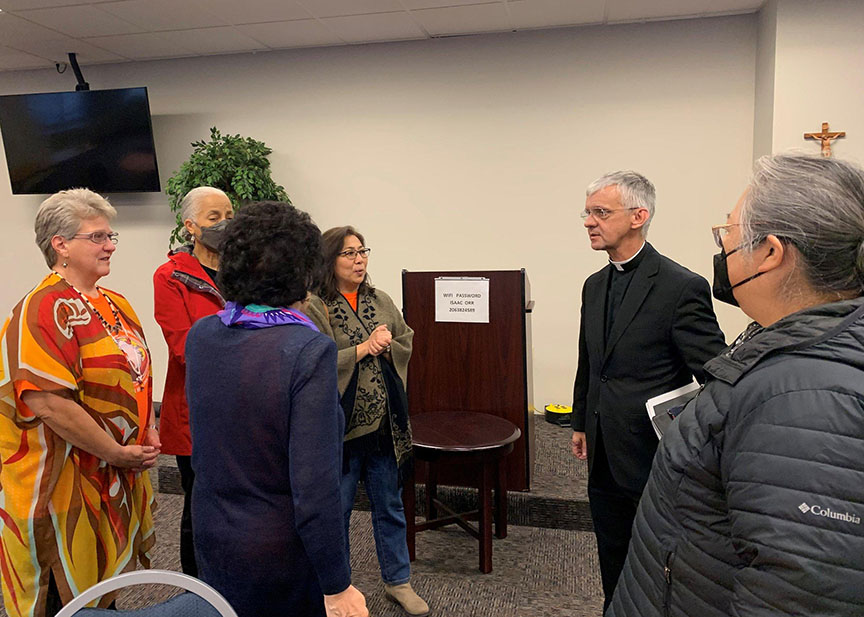

The priest was invited to speak by the Seattle Archdiocese’s Native American Advisory Board in partnership with the archdiocese’s Multicultural Ministries team.

Kiara Raven, an advisory board member, said Father Carson was able to speak about “the Catholic Church’s history in relation to Natives without causing deep guilt to non-Natives or Catholics.”

In his presentation, Father Carson explained the history of residential boarding schools for Native Americans. He also detailed the U.S. bishops’ recommendations on how to promote healing with Native people through listening sessions, relationship-building, archival research and cooperation with investigative bodies.

The program sparked questions and comments from audience members, many of them associated with Northwest tribes, who pointed out that not every experience was traumatic and not everyone is totally demoralized.

Raven called Father Carson’s presentation a “gift.”

Joining the program were Archbishop Paul D. Etienne and Auxiliary Bishop Eusebio Elizondo, both of Seattle, and Father Patrick Twohy, who has served tribes in the Pacific Northwest for more than 40 years.

Father Carson said the boarding schools were created in response to early 19th-century efforts by the federal government to pacify tribes through education.

The focus was on erasing Native culture to prevent tribes from attacking and, he said, “because they had this idea that the Native culture was dying out, they thought they were helping them out by giving them European culture.”

Many of the schools were modeled on army camps, with harsh living conditions, forced manual labor and physical punishment. When Native parents refused to send their children, some federal Indian agents forcefully removed children, even kidnapping them, the priest said.

Native families’ dependence on the government for food was used as leverage, Father Carson explained: “They said, ‘We won’t give you more until you give us your kids.’”

The federal government controlled the boarding schools but relied on religious organizations to run them, he said. Because of broad anti-Catholic sentiment, most of the early schools were administered by Protestants and Quakers.

“When the Catholic Church comes in with the Indian agents, they were violating their own morality and ideology” by complying with the cultural thinking of the time and enforcing governmental policies that forbade Native language, Native culture, and Native religion, Father Carson said.

“Racism is a serpent that runs through this boarding-school period,” he added.

The efforts to suppress Native culture led to poor self-image, laying the groundwork for historical trauma still suffered today, he said.

“When you’re always told your family is bad and you’re bad, you grow up with some self-hate and that develops into psychological trauma,” Father Carson explained.

The priest also explained how the USCCB is working to enact recommendations that help promote listening and healing including:

- Tribal listening sessions that focus on working with tribes to develop the agenda and “listen to where the Spirit leads and validate feelings, which are neither good nor bad.”

- Better relationships with tribes through shared community spaces, cultural events, and other efforts “to build relationships and trust.”

- Archival research that starts or continues the process of locating records related to Native American history in a diocese.

- Cooperation with investigative bodies – federal and tribal – because “the search for truth helps everybody.”

Although these steps will support the healing process, healing is not a one-time event, Father Carson said.

“We are people of faith,” he said. “When we address healing, it comes from the core of being Christ-centered. All our actions are first and foremost as people of faith.”