As the COVID-19 pandemic made its way around the globe in 2020, people of all races, ages and walks of life watched and waited. A new virus unpredictably and recklessly invaded life as we knew it, and a fearful uncertainty took root. In this time of crisis, people wondered anxiously what direction their lives might take next.

Tragically, COVID-19 spelled death for vast numbers. Families grieved as the virus struck with what felt like malicious injustice.

For so many the pandemic also resulted in unemployment, a loss of health benefits and the terrifying prospect of becoming unable to provide for their own needs and their families.

COVID-19’s wreckage was multifaceted. Pandemic pain often meant that familiar ways of doing things no longer could be ways of doing things at all, at least for the time being.

Like so many others, my wife and I, both retired, sheltered at home for weeks and weeks, doing our part to fight the pandemic’s spread. Our social distancing kept us away from our children and their families. We deeply regretted not being able to participate in the high school graduations of our two oldest grandchildren.

But yes, the internet phenomenon known as Zoom gained a foothold in our home. We “saw” family and friends again and again, though we could not reach out and touch them.

Curiously and amazingly, as social distancing kept people apart, human ingenuity leapt forward with new ways to connect us. In this time of widespread suffering, isn’t it remarkable how the need for human community asserted itself?

“In the midst of loss, uncertainty and suffering, something incredible is happening: We are noticing the bonds which form our human family,” Filipino Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, who heads the Vatican Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, commented in April. He observed:

“As we live in isolation and we all become marginalized and vulnerable, the global suffering we are seeing has made it startlingly apparent to us that we need other people and other people need us too.”

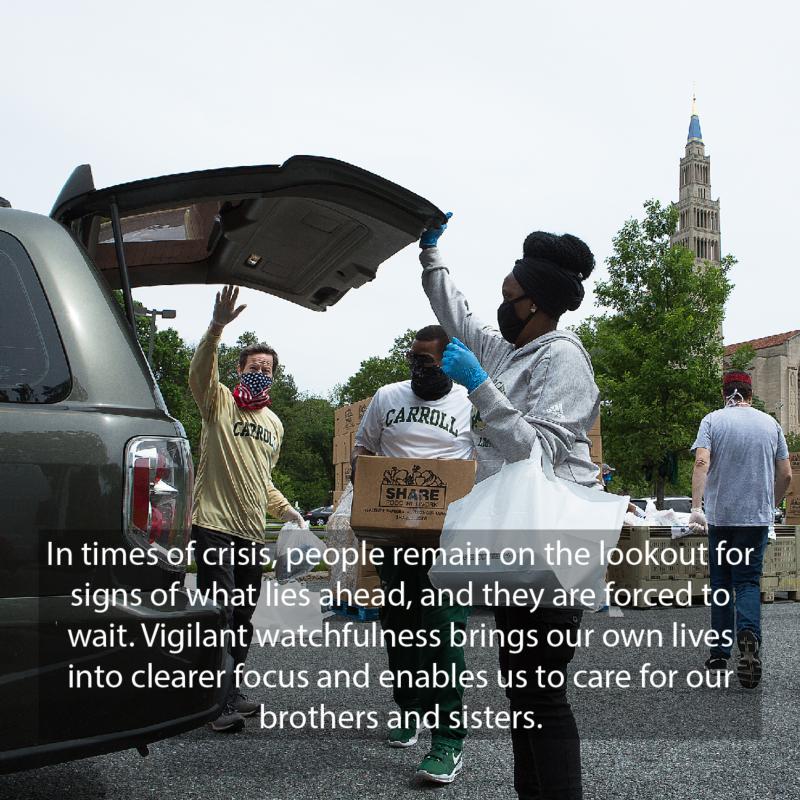

In times of crisis, people remain on the lookout for signs of what lies ahead, and they are forced to wait. But what do we await? That is a difficult question. But a crisis, by definition, is not just a time of trouble, pain or seemingly insoluble challenges.

Cardinal Tagle acknowledged this by characterizing the 2020 pandemic as a “turning point,” albeit one that “is throwing our lives and societies into chaos.”

But what kind of turning point? A crisis can leave people feeling uncertain where to turn at all. What can they do to anticipate or assure the best possible outcome of events?

Christians have an annual season of waiting and watching vigilantly. It is Advent, a season that looks beyond itself to Christmas and the birth of Jesus.

To wait and watch, however, is not to become passive, unreflective or isolated, Pope Francis has suggested. In his first Advent as pope, he referred to watching as “the virtue, the attitude of pilgrims.” He asked, “Are we watching or are we closed?” Also, “are we pilgrims or are we wandering?”

If vigilant watchfulness brings our own lives into clearer focus, it can bring the lives of others into clearer focus as well. Advent’s goal is not to foster greater isolation, the pope seemed to suggest at the start of Advent in 2019.

This is a time to become fully awake, to rise from slumber, he indicated. “The slumber from which we must awaken is constituted of indifference, of vanity, of the inability to establish genuine human relationships, of the inability to take charge of our brother and sister who is alone, abandoned or ill.”

However, “keeping watch does not mean to have one’s eyes physically open, but to have one’s heart free and facing in the right direction, ready to give and to serve,” Pope Francis explained.

I wonder what kind of story today’s young people will tell to their grandchildren decades in the future about the 2020 pandemic. It certainly will be the story of a wretched illness that wreaked tremendous harm.

Will it also be the story of a crisis that prompted people everywhere to reconnect with old friends near and far, and to rejoice in rediscovering the better parts of themselves — capabilities in the realms of hope and goodness too long neglected?

Boston’s Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley wondered this Easter whether the coronavirus crisis may be “the cross that we are being asked to carry,” as Simon of Cyrene was forced to do for Jesus at the time of his crucifixion.

“It is not hard to imagine” that as an old man Simon may have told his “children and grandchildren” about all the good that came of this “worst day of his life,” the cardinal remarked.

The cardinal looked forward to “a moment when we can look back at our history and say that this terrible scourge … will have made us better people, more loving, more generous, more courageous, less materialistic, less individualistic, less self-centered.”