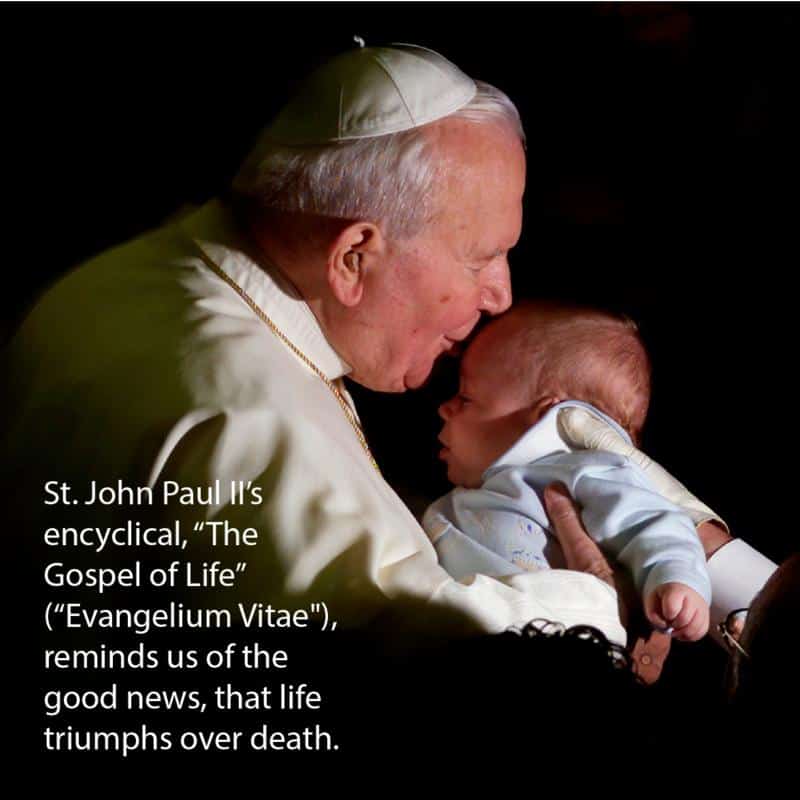

One of my assignments as a theology graduate assistant was to deliver a 90-minute lecture on St. John Paul II’s 1995 encyclical “Evangelium Vitae” (“The Gospel of Life”). The task was daunting: Not only was I to unpack more than 45,000 words, but I was to make the church’s case for protecting life in highly personal circumstances, from reproductive decision-making to end-of-life care.

Watching students respond positively to it was pivotal for me; it launched me into a teaching career focused on Catholic bioethics and moral decision-making.

As I reflect on the legacy of the document on its 25th anniversary, it’s clear that all people of goodwill, not only people interested in theology, would benefit from encountering or revisiting its prophetic message of what it means to be consistently and joyfully pro-life.

According to St. John Paul, to be pro-life is not to start with moral claims or a list of issues to accept or reject, but instead it is to begin with the God revealed by Jesus Christ and his plan for every person — salvation and eternal life.

Our God is a God of living, so where there is human life, there is something of “incomparable worth.” Our responsibility to our brothers and sisters and the dignity of every life shape how we approach all moral issues, whether sexual or social, personal or communal.

“Evangelium Vitae” takes a sweeping look at contemporary threats against life, which create what St. John Paul calls the “culture of death.” The issues he cites are many, including the unjust distribution of resources, the arms trade and armed conflicts, the “reckless tampering” of the “ecological balance,” the drug trade and sexual activity that risks human life in its earliest stages.

Add a refugee crisis and economy that disproportionately affect the poor and you have the issues to which Pope Francis has been drawing our consciences. The culture of death, the culture of indifference, the throwaway culture: a quarter century later it persists, no matter what we call it.

The encyclical focuses the bulk of its attention on the gravest threats to life that involve the direct killing of people. They are couched in the story of Cain and Abel, in which the killing of brother by brother reveals a rupture in the communion that God intended for us.

The two issues to which St. John Paul devotes the most attention are abortion and euthanasia, which involve the direct killing of a human being in two of its most vulnerable stages: its beginning and end. He argues that these actions have become sanitized to the point that many no longer recognize them as murder.

Instead, they are increasingly protected in law as if they were rights and characterized as health care by some in the medical community. Adding to their moral gravity is the fact that they take place in the context of familial relationships: Nature normally impels us to protect the lives of our kin, not to end them.

But St. John Paul does not end on a note of despair. He challenges readers to contemplate how they can build up a “culture of life.” Christians must push back against secularism, which promotes materialism and relativism, and which obscures moral truths.

Scientists, medical professionals and engineers must ensure that technology and health care are aimed at human flourishing.

Teachers and catechists must help younger generations understand and recognize anthropological and eternal realities. And families must commit to being “sanctuaries” of life, where children experience firsthand the dignity of human life and learn to protect it.

Twenty-five years later, threats to human life remain and are growing. Yet “Evangelium Vitae” reminds us of the good news, that life triumphs over death. The pro-life witness — which sees the sacred in unexpected places and people, and joyfully protects them with loving care — is needed still.

A culture of life is always within reach and is built one moment and decision at a time.