VATICAN CITY. Some 80 years ago this week, before Pope Francis told priests to be “shepherds with the smell of the sheep,” his wartime predecessor left the Vatican to walk the rubble of Rome’s peripheries after bombings during the Second World War to show his solidarity with his flock.

While some commentaries about his legacy during World War II remain mixed, Pope Pius XII is still heralded by Romans, and the city itself, as the “Defensor Civitatis” or “protector of the city.” And 80 years after the first bombs dropped on Rome, an exhibit near the Vatican organized by the Museum of the Popes project celebrated that status by recalling the efforts of Pope Pius to defend the city that envelops the Vatican.

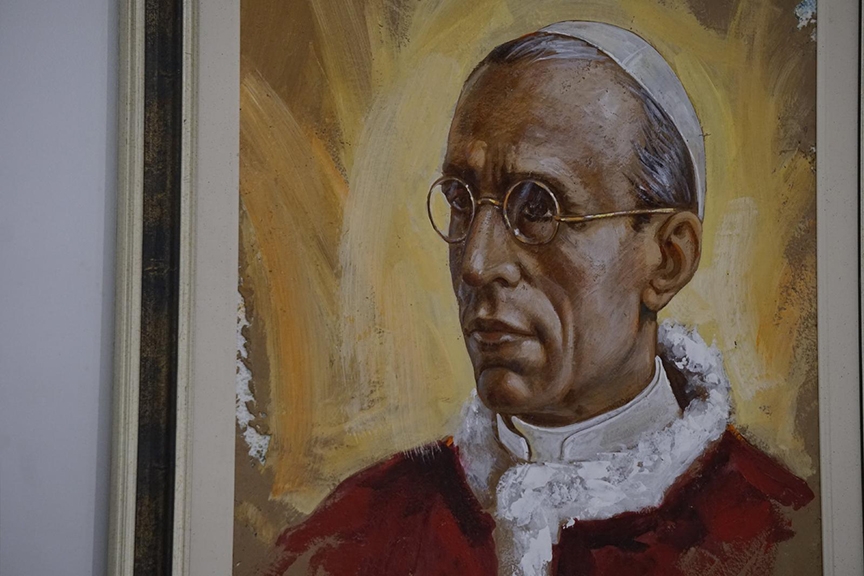

The exhibit, titled “Defensor Civitatis,” displayed objects and photographs of Pope Pius’ life and pontificate that were privately donated from individuals close to him.

Ivan Marsura, director of the museum project, told Catholic News Service May 23 that one of the reasons Pope Pius was praised by Romans is because many popes had a history of fleeing Rome during conflict, and “he was the one who didn’t escape the city” when the war reached Rome.

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was meeting with Adolf Hitler in northern Italy when the Allies bombed Rome July 19, 1943, killing 1,500 people. Shortly after, Mussolini was voted out of power by the Grand Council of Fascism, arrested and sent to prison on an island off the Italian coast.

Italy’s King Vittorio Emanuele III was widely blamed for not defending Italy against fascism and letting it enter unnecessarily into war. He was reported to have started making his way to areas impacted by the bombing but turned around when people began throwing rocks at his limousine and shouting insults at the king riding inside.

It was therefore Pope Pius who, visiting the bombed San Lorenzo neighborhood of Rome near the city’s main train line, became identified as the city’s protector.

In her memoirs, Sister Pascalina Lehnert, the pope’s German assistant, recalled how after hearing the bombs on July 19, 1943, Pope Pius told his driver to prepare the car, grabbed whatever money he could find to hand out, and left immediately to go to San Lorenzo without telling anyone. Only after seeing the car take the pope across St. Peter’s Square and out of the Vatican did she notify Cardinal Cardinal Giovanni Montini, then-Vatican secretary of state and the future St. Paul VI, that the pope had left the Vatican.

Images of Pope Pius’ July 19th visit and a second public appearance in front of the Basilica of St. John Lateran on August 13, 1943, show the pope among the masses with no security separating them. In one photo outside the basilica, the pope is seen holding a stack of lire – Italy’s currency prior to its adoption to the euro – which he gave to a parish priest to pay for the damages to his community. In this second visit Cardinal Montini is pictured at the pope’s side.

Amid the chaos of August 13, Marsura explained, the car used to take the pope to the bombed neighborhood had broken down and someone from the crowd offered their car to the pope for his return to the Vatican. Images from that moment show people looking upward – not at the pope but to the sky, since planes were still flying over the city, any of which could have dropped bombs.

Beyond gestures of solidarity with the people, in May 1943 the pope had also appealed directly to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to spare Rome from bombings. The president said in response that allied pilots had been instructed to “prevent bombs from falling within Vatican City.”

Despite this assurance, the pope and his people, as bishop of Rome, remained in an active war zone and bombs fell twice in the Vatican in November 1943 and March 1944, damaging office buildings and killing one person.

Additionally, Marsura said the pope “was informed that Hitler wanted to abduct him, and he signed a document saying that if he was abducted by the Germans his reign as pope would end and he would be a simple cardinal. The other cardinals could then elect a new pope.” While historians still debate the authenticity of the abduction plot – some say it was a rumor devised by British intelligence – Marsura said the pope’s reaction to it “showed the desire of the pope to stay in Rome despite the problems and difficulties he knew he was facing.”

The pope’s presence in Rome and his lobbying to the Axis powers and Allies for Rome to be declared an open city resulted in a “miracle,” according to the late Arcangelo Paglialunga, eyewitness to Rome’s liberation in 1944 and a longtime Vatican journalist. He told Catholic News Service in 2004, “Pope Pius XII had done so much. Just think, the last Germans left Rome the evening of June 4th right at the same time the first Americans were coming in. It seemed like a miracle that not a shot had been fired. Nobody died. This was the miracle of Rome.”

As leader of the Catholic Church during World War II, Pope Pius has received mixed analysis of his actions during the war: he worked through diplomatic channels to push for peace as head of a country that declared itself neutral in the conflict between the Axis powers and the Allies, but he also chose not to openly condemn the murder of six million Jews across Europe and North Africa. And that history is becoming only more complex as new information and analysis comes to light from scholars recently given access to documents from the wartime pontificate of Pope Pius for the first time in 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed the pace with which scholars could come to Rome and study the newly released archives, but new findings continue to trickle out and are expected to follow in coming months.

So while there are still questions today about his inaction against the Holocaust, Marsura explained that the pope’s efforts to defend the city was immediately recognized by the people of Rome.

When the city was liberated by Allied forces June 4, 1944, Italians waved banners that read “Pius: Protector of the City” and “Long live the pope.” After his death the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, ran the headline “Shepherd and Protector of the City.”

Tens of thousands of people gathered in St. Peter’s Square the following day to receive Pope Pius’ blessing. The large square in front of St. Peter’s has since been named “Piazza Pio XII” in his honor with the title “Defensor Civitatis” beneath his name. Sister Lehrnard wrote that “all of Rome gathered in the square to thank the Holy Father,” that June 5.

“It was thanks to him that the city was saved,” she said. “Forever he will remain in history as the savior of Rome.”