When Jeh Vincent Johnson died last month at age 89, he was remembered as a prominent architect and educator, well-respected and revered in his field. The son of the first Black president of Fisk University, he was raised in Nashville but had not lived in the city for many years.

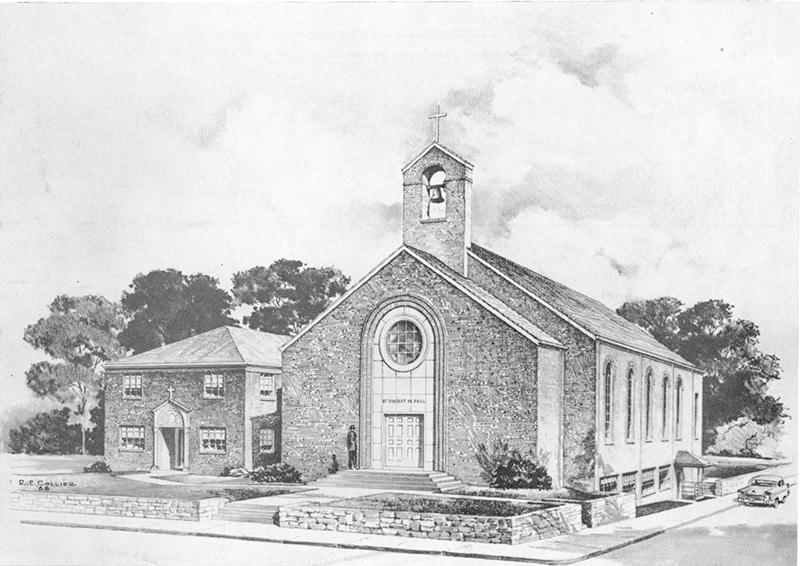

When it was time to plan his funeral services and burial, his family brought Mr. Johnson home to his childhood parish of St. Vincent de Paul, and laid him to rest in Nashville’s historic Greenwood Cemetery.

Johnson’s son Jeh Charles Johnson, the former U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security, reached out to Deacon Bill Hill, formerly of St. Vincent Parish, to lead a graveside service for his father. “I didn’t personally know the family, but I know that St. Vincent was important to them,” Deacon Hill said.

After graduating from St. Vincent and Pearl High School, Mr. Johnson went on to graduate from Columbia University and then taught at Vassar College for 37 years. But he always pointed back to St. Vincent as his educational foundation, Deacon Hill said.

A haven for HBCU families

When schools in Nashville and the region were still segregated, St. Vincent de Paul School was known to many in Nashville’s Black community, in particular those affiliated with the city’s historically Black colleges of Fisk, Tennessee State University, and Meharry Medical College, as the premier elementary school in the city to educate their children.

At the time young Jeh V. Johnson started school at St. Vincent, which operated from 1932-2009, it was one of the only private schools in Nashville open to Black children, along with Holy Family and Immaculate Mother Academy, all part of the Diocese of Nashville.

The schools, established by St. Katharine Drexel and her Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, served minority children from the neighborhood and beyond, poor and middle class alike, regardless of their religious background.

Johnson’s parents were not Catholic, but they sent their son to St. Vincent, confident that he would get a good education under the tutelage of the Sisters. Along the way, he was baptized a Catholic.

His father, Charles S. Johnson, a sociologist and African American scholar, came to Fisk University in 1928 to head the newly established Department of Social Sciences. In 1937 he became the first Black elected vice president of the American Sociological Society.

In October 1946 Johnson because the first Black president of Fisk and served in that position until his death in 1956.

According to Fisk’s archive collection on Johnson, “While president at Fisk he established its Academic Development program with headmasters, a tutorial system, and the Race Relations organization. Johnson was also the creator and editor of Opportunity Magazine, a journal dedicated to empowering African-Americans.”

“Charles Spurgeon Johnson was a leader in making Fisk University the major Negro center for social research in the South and one of the outstanding research institutions in the entire field of race relations,” the archives continue.

Dr. James Lawson, who taught at Fisk, Tennessee A & I University (which later became TSU), and served as president of Fisk from 1967-1975, sent his son Ronald to St. Vincent.

“He was probably the best basketball player ever at St. Vincent,” Deacon Hill said of Ronald.

He attended one year at Father Ryan High School, but at that time Black students were still not allowed to play sports, so he transferred to Pearl High and helped them win two national championships. He went on to play for UCLA under legendary coach John Wooden.

Lawson returned to Nashville to coach Cameron High School to two state championships, and then coached the Fisk men’s basketball team to a league championship. He was posthumously inducted into the TSSAA Hall of Fame in 2008.

‘Steeped in community’

Dr. Reavis Mitchell, who served as Dean of the School of Humanities and Behavioral Social Sciences at Fisk University, was another prominent member of Nashville’s Black academic community with strong ties to both Fisk and St. Vincent.

When Mitchell died last summer, his son Regan Mitchell recalled that being part of the Catholic faith meant being “steeped in a community,” especially the community of St. Vincent. “It was a very beautiful thing” to him.

Dr. Mitchell attended St. Vincent de Paul Church and School growing up, and his mother attended Immaculate Mother Academy, and was an original member of St. Vincent in the early 1930s, both founded by St. Katharine Drexel and her Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. When the Mitchell boys were younger, “our life revolved around St. Vincent,” said Mitchell’s son Roland.

When he was a graduate student at Tennessee State University, Dr. Mitchell wrote his masters’ thesis on “The involvement of the Catholic Church with the Black community in Nashville, 1954-1970,” where he examined the uneven relationship between the institutional church and its Black members.

He previously spoke to the Tennessee Register about the important role St. Vincent de Paul School played in the community. “So much proselytizing of the Catholic Church is done through the schools.”

For generations of Black Catholics, attending Catholic schools, and being part of the Catholic church “prepared you well for the middle class,” Mitchell said.

Know your history

The history of St. Vincent de Paul School may not be well known to newer members of the diocese or the wider community. That’s one reason Deacon Hill is sharing that history with others through Christ the King Church’s Black History Month series, “From dark past to present hope: Hearing Nashville’s Black voices.”

On Feb. 14, Deacon Hill presented “Shaping the Black Catholic Church: The story of St. Vincent de Paul Parish and the Church of the Holy Family,” exploring the histories of the original Holy Family Parish in downtown Nashville, and St. Vincent, the diocese’s second historically Black parish.

On Feb. 28, Deacon Hill will present “The color of Catholic education: Desegregation in the Diocese of Nashville,” which will explore the diocese’s response to the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

An alumni of St. Vincent de Paul School and Father Ryan High School, Deacon Hill first began researching and documenting the Black Catholic history of the diocese for his master’s thesis at St. Meinrad School of Theology.

When Deacon Hill’s academic advisor, the late Father Cyprian Davis, asked him about the Black Catholic history of Nashville, “I realized I didn’t know my own history,” of his home parish and school, he said. Father Davis, a renowned scholar of Black Catholics in the U.S., “knew more than I did,” Deacon Hill said. “It’s important to know where you come from, where you are, and where you’re going.”

All presentations in Christ the King’s Black History Month series, including the one from Feb. 21 by Paige Courtney Barnes, “Fortifying justice with fraternal charity,” and two talks given earlier in the month by TSU professor Dr. Learotha Williams on the history of the African American experience in Nashville, can be accessed at: https://www.ctk.org/anti-racism-initiative.