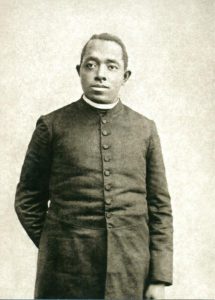

CHICAGO (CNS) — Father Augustus Tolton, the first identified Black priest ordained for the United States, would likely be disappointed by what he sees going on in the United States today, said Father David Jones, pastor of St. Benedict the African Parish in Chicago.

“I think ‘disappointed’ is a key word. I think people can understand that and it helps to tie into the frustration that Black people are feeling and always experiencing.” Father Jones said.

The Archdiocese of Chicago opened Father Tolton’s cause for canonization in 2010, and Pope Francis declared him “venerable” in June 2019, after a theological commission has unanimously recognized his “virtuous and heroic life.” Two steps of the process remain — beatification and canonization. In general each step requires confirmation of a miracle attributed to the sainthood candidate’s intercession.

As the first Black priest ordained for the United States, Father Tolton struggled against rampant racism in the years following the Civil War but was known for bringing people of all races together. For that, he was persecuted by his brother priests and people in the white community of Quincy, Illinois.

The priest, also known as Augustine, was born into slavery in 1854 and died in 1897 at age 43. He was denied access to seminaries in the United States after repeated requests, so he pursued his education in Rome at what is now the Pontifical Urbaniana University.

In many ways, the unity Father Tolton worked for is still out of reach in the church and society, Father Jones told the Chicago Catholic, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Chicago.

“We sit in churches on Sundays and we’re OK with how segregated we are in church,” he said. “That shouldn’t be. We shouldn’t be OK.”

The priest pointed out some basic steps that could be done to address this problem, starting with liturgical music.

“You know we have very little in our Catholic resource of liturgical music for pastoral purposes that comes from African American composers. So, we always, from this part of this part of the world, have to go the Protestant community to get music and fit it into a Catholic liturgy,” Father Jones said, before adding: “We can do better than that.”

Father Tolton’s example of welcoming people of all races to Mass also makes sense to Father Jones, who acknowledges the church still has work to do in this area.

He said even now “there are still lots of (Black) folks who are Catholic who tell you the stories about what was said to them when they tried to go to Mass at a certain parish.”

Chicago Auxiliary Bishop Joseph N. Perry, postulator of Father Tolton’s canonization cause, believes Father Tolton can be an example for people during this time of racial division.

“In him, I think we see a priest-pioneer of reconciliation,” Bishop Perry said. “We hope that he looks down upon us and sees this as a wounded country from his place amongst the saints and angels. I think this is where we can plead for mercy and holy assistance from him in this time of racial crisis.”

The bishop also said the saint is an example for what it means to be a Catholic.

“He really had a love for the Catholic Church. He believed that the Catholic Church had the means, really, to unite people of every race and give everybody the dignity that’s due everyone,” he said. “His own pastoral practice drew men and women of whatever skin tone together under one roof and that’s what got him into trouble down in Quincy.”

Bishop Perry said one area where the church could effect change is “spatial racism,” which relegates poor people of color to living in certain neighborhoods.

“Chicago is known to be one of the most segregated cities in the country. We’re playing this racial hopscotch all the time, where as soon as Blacks or Hispanics move in, whites move out. And it never stops,” he said. “Are we saying enough in our pulpits about it? Are we saying enough in our religious education programs with young people?”

The law says people have to work and live together equally, but at the end of the day everyone goes home to their racially segregated neighborhoods, he said.

“Even our Sunday worship is divided,” he said. “This whole experience of single-racial parishes we should understand is really kind of abnormal. They don’t echo the Pentecost event, which started the church to begin with.”

At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descended upon the disciples and they were able to preach in the various languages of people gathered in Jerusalem, people who looked different from one another. They were all united around Christ.

“You’d think for all of our education, our own social awareness and for all of the ease of communications that we have, that some of these boundaries and borders between us and amongst us would have been erased,” Bishop Perry said. “But it seems to have stirred more fear of people toward one another, unfortunately.”

Valerie Jennings, an archdiocesan parish vitality coordinator, said she has experienced that fear all of her life as a Black woman in Chicago.

She spoke of a recent encounter with a white woman while she and her husband were walking their dog in the largely white affluent suburb where she lives. Jennings was a safe distance away from the woman but when the woman saw her and her dog, the woman yelled at her to keep her dog away and shouted: “You people, what are you doing here?”

It’s an encounter that still puzzles and troubles her. Jennings also talked of experiences attending Mass at white parishes as the only Black person in the congregation.

“You try to say good morning and they just give you this look. I don’t know what they are thinking. It’s very unwelcoming,” she said. “I can see how these single-race parishes came to be because white people didn’t want us around them. When I think of what happened to Father Tolton in Quincy, they did not want him anywhere around them. He was basically chased away.”

Jennings said Father Tolton would be wondering why more hasn’t been done to embrace people of all races since his time.

“We have an opportunity right now to change the narrative and the experience of Father Tolton,” she said, adding: “I see more universality in the marches going on right now than I see on Sunday morning.”

She also thinks the priest on the path to sainthood might also see the positive aspect of the peaceful protests for racial justice. “I’m hoping that Father Tolton is clapping his hands and jumping for joy saying, ‘See my people and not just Black people — but see my people.'”