Many people suffer the loss of “a sense of place” when a region that is like home to them is exploited or abused in large ways.

Places that afford us a sense of place have played major roles in our lives. They mirror key dimensions of our identity back to us.

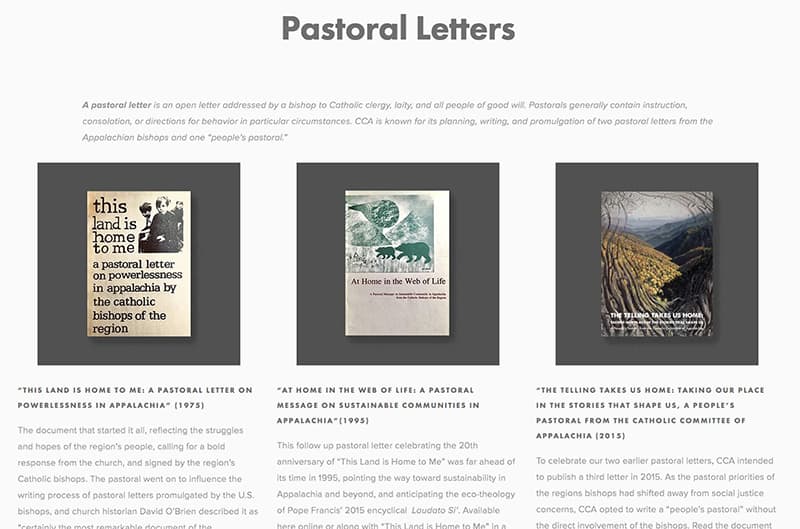

Many in the U.S. region called Appalachia know what the loss of a sense of place means. The Catholic Committee of Appalachia said in its 2015 people’s pastoral letter titled “The Telling Takes Us Home” that harmful mining practices and other damage to streams, towns or mountain vistas harmed not just “the landscape.”

Rather, some developments, like “extreme mining activity,” exacted a toll on the “sense of place and of home.” Those living in Appalachia’s mining areas “and beyond often grieve the loss of home as they would the loss of a dear friend.”

For 50 years the Catholic Committee of Appalachia has served as an advocate for this region. “The truth of Appalachia is harsh,” its first pastoral letter affirmed.

Released in 1975 and signed by 25 Appalachian bishops, it was titled “This Land Is Home to Me.” It explored a sense of powerlessness in this often forgotten region, which it called “the spiny backbone of the eastern United States.”

It stressed that “the suffering of Appalachia’s poor is a symbol of so much other suffering.” It stands as a “symbol of the suffering which awaits the majority of plain people in our society if they are laid off, if major illness occurs, if a wage earner dies or if anything else goes wrong.”

Thus, “at stake is the spirit of all our humanity.” Indeed, said the pastoral letter, “there are too few spaces of soul left in our lives.”

I contributed a chapter to a 1987 book titled “A Sense of Place.” Visiting any locale that evokes this sense is always more than “a trek into the past,” I wrote. It means revisiting one’s roots.

These are places populated in our memories by people who fulfilled unforgettable roles in our lives.

During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, while my wife and I, for reasons of health safety, were unable to participate in our parish’s Sunday Mass, we turned to Sunday Masses livestreamed by St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota, some 1,200 miles from us.

My alma mater is the university this Benedictine abbey conducts. Its well-known contemporary church designed by Marcel Breuer was completed during my student years.

Upon logging into the Sunday Mass, I immediately felt at home. I experienced the indelible sense of place I’ve described. I wrote in the book chapter:

“St. John’s is a place, a small place. A boy of 18 goes there to spend four of the most formative years of his life. When he leaves, his world has grown much larger.”

But imagine sometime finding this place converted unrecognizably (for business or other reasons) to some entirely different purpose. My sense of loss would prove overwhelming.

Unsurprisingly, the Catholic Committee of Appalachia’s “people’s pastoral” spoke of such loss, explaining:

“Studies have confirmed higher rates of depression in the coalfields, often related to this loss of place. People of faith would be right to consider this grief a kind of spiritual death.”

The Catholic Committee of Appalachia plays a vital role in making its region’s compelling story widely known. If it is a story of fearsome shadows cast over workplaces, homes, neighborhoods and stunning mountain ranges, it is a story also of the efforts undertaken to create sustainable communities of many kinds and restore hope.

“There is a growing sense of apocalypse, the gradual revelation that the old order of things is coming to an end. … But beyond apocalypse … a new world is being revealed, and this should give us hope,” the committee’s 2015 message forcefully stated.

An accent on social justice characterized the 1975 pastoral letter. Twenty years later a second pastoral letter focused equally on care for the earth, a form of caring intertwined essentially with care for human life.

Titled “At Home in the Web of Life,” it insisted that economics “should not undermine human dignity and community, nor the dignity and community of nature. It needs to remain rooted in the web of life.”

It is fascinating to note points of convergence between the work of the Catholic Committee of Appalachia and Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical on the environment, “Laudato Si’.”

“The history of our friendship with God is always linked to particular places which take on an intensely personal meaning,” Pope Francis remarked. For “anyone who has grown up in the hills or used to sit by the spring to drink,” returning to such “places is a chance to recover something of their true selves.”

Regrettably, care for “our common home” is deficient nowadays, Pope Francis made clear. Recall, he urged, that “the entire material universe speaks of God’s love. … Soil, water, mountains: Everything is, as it were, a caress of God.”